Diamonds – Purest carbon

July 13, 2012Leatherback turtles – Why are they dying on our coastline?

July 13, 2012By Hu Berry

What makes men leave the familiar comforts of their homeland to venture to a land known as the Dark Continent – Mr Berry looks closely at some of the explorers who showed courage enough to explore the unknown, inhospitable and life threatening conditions of early Namibia.

The first explorers returned home with harrowing tales of thirst, hunger, wild beasts and, sometimes, savage people. Those who followed must have known what to expect, yet their curiosity could only be quenched by personally embarking on their own voyage of discovery.

Circumvention of Africa by Phoenician sailors may have taken place two centuries before Portuguese navigators rounded the Cape.

Understandably there remains no record of them landing on Namibia’s foreboding coastline.

What then placed Portugal at the forefront of European nations exploring this remote world?

Confronted by often actively hostile Spanish neighbours and Muslim states, Portugal looked to the sea for essential trade of her salt, wine and olive oil in exchange for exotics. Possessing mostly meagre pastures and largely infertile land, the sea ensured a rich harvest.

Master mariners soon took to the stage, looking southwards past the Canary Islands.

History records that three wooden caravels, manned by the best pilots and masters available, set sail in 1485 under orders of King João II.

Carrying heavy limestone crosses (padraõs) to plant and establish claim to new lands, the expedition, led by Diego Cão, was greeted by lush, tropical shores, massive river mouths and unexpectedly friendly tribes.

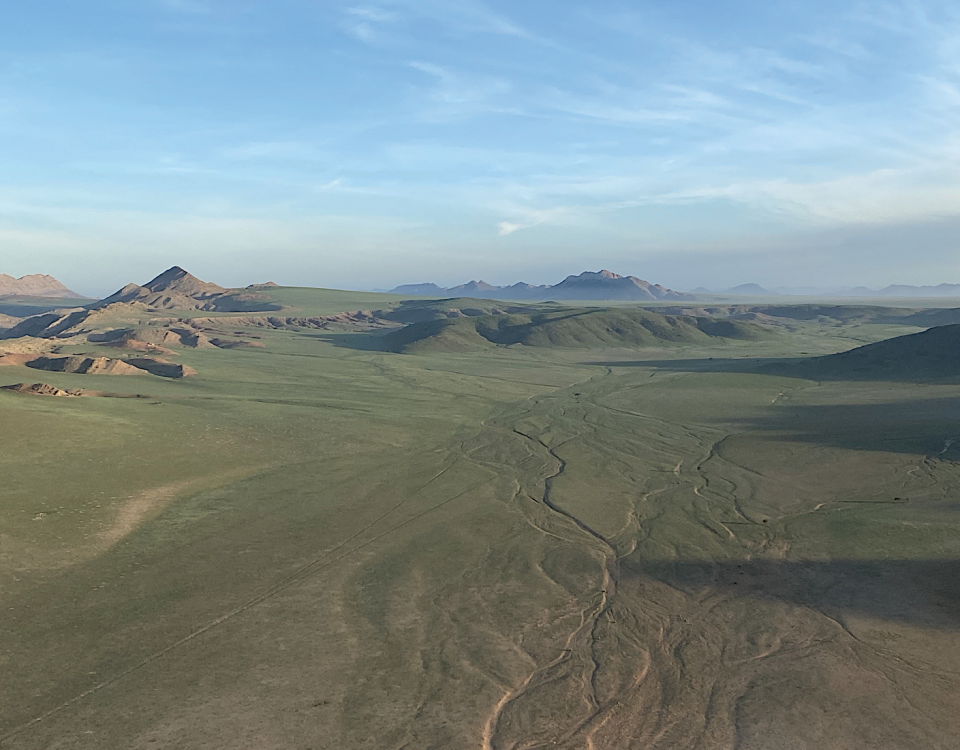

Southwards this landscape gave way to an inhospitable, waterless, barren coastline where thick fogs shrouded treacherous reefs and hidden sandbanks created a deathtrap for any ship running aground – they had reached Namibia’s notorious Skeleton Coast.

(Read Hu Berry’s shipwreck story – the legacy)

January 1486 is when Cão planted the last of his padraõs on Cape Cross’s wind-chilled, rocky headland.

He apparently died in this vicinity, near the Serra Parda (Dark Mountains), possibly the present-named Spitzkoppe that appear dark in colour when viewed from the shoreline. The Portuguese transcription on the cross said:

‘In the year 6685 of the creation of the Earth and 1485 after the birth of Christ

the most excellent and most serene

King Dom João of Portugal ordered this land to be discovered and this padraõ to be placed by Diogo Cão, gentleman

of his house.’

Other illustrious voyagers, such as Bartholomeu Dias, navigated in Cão’s wake, making landfall in Walvis Bay in 1487 before sailing south to anchor in the windswept bay of Lüderitz.

Dias later rounded the Cape of Storms, planting his cross at Dias Point near Lüderitz on his return. Cão’s original padraõ stood 400 years without mention, until Captain Messum made landfall there in the 1840s and proceeded overland to the Brandberg.

He was so impressed by its ramparts towering above the desert that he somewhat egoistically named it Mount Messum.

His name was later transferred to the less impressive, nearby Messum Crater. To the credit (and astonishment) of Messum, he recorded the presence of people, Berg Damaras, herding sheep and goats.

They already knew the nutritious value- of !nara seeds from the unique desert melon, which formed part of their frugal diet. Messum also encountered Strandlopers (beachcombers) relishing dried, but odious fish during his explorations to the Kunene River mouth.

When Germany began flexing its colonial aspirations, Chancellor Bismarck sent the gunboat Wolf under the captaincy of von Raven to take possession of the land ‘from 26 to 18 degrees south, with the exception of Walvis Bay, German Protectorate’.

These latitudes did not include the furthermost northern and southern sections of Namibia’s present coastline, however.

The brief, 30-year occupancy of German South West Africa began in 1884. Walvis Bay was necessarily omitted because Great Britain, under the stern gaze of Queen Victoria, was basking in the might of her maritime power and had already annexed the strategic port and its enclave of 1 124 square kilometres in 1840, during the so-called scramble for Africa. Britain’s strategy was to forestall German ambitions and to ensure right of passage for British ships rounding the Cape.

Northern explorations

At the turn of the 19th century, riding camels and oxen, some explorers, like Dr Esser of Berlin, went as far north as the Kunene River mouth.

After witnessing the desolation and howling winds that drenched his expedition with sand, he decided against further trips along its bleak beaches.

Others were not to be deterred. During the 1890s the illustrious geologist, Dr Georg Hartmann, undertook the most embracing assessment of the Skeleton Coast that had been made to date. His goal was to locate sites suitable for a harbour and to find viable deposits of bird guano.

Like other valuable elements of the earth, guano is classified as a mineral and was mined as such. He, his party of German cavalrymen and natives of the area combed the desolate wilderness between Cape Cross and the Kunene. Not only did they overcome what the elements flung at them, but they accessed the formidable Kaokoveld, using its ephemeral riverbeds as avenues of exploration into the interior.

Their accomplishment is heightened by what they had to contend with. Lions prowled their campsites at night, elephants trumpeted their displeasure, dehydration and gnawing hunger set in for both man and trek ox.

Hartmann’s contingent would have taken little comfort from the fact that, 20 years earlier, a mission of a different nature had successfully completed the route that their ox wagons struggled against.

Riding roughshod and relying solely on horses for speed and endurance, a party of hardened Boers led by the legendary Gert Alberts had already penetrated to the isolation of Rocky Point on the Skeleton Coast. Alberts was spear-heading a possible route for the main body of Thirstland Trekkers, who were determined to escape domination by the British presence in South Africa.

From the south in 1836 came Captain James Edward Alexander, soldier, traveller and scientist, under the patronage of the Royal Geographical Society, London. His ardour is reflected in the two-volume account of his experiences during this classical overland journey.

His route took him from Cape Town via the harsh wastes of the southern Namib, then known as Greater Namaqualand. At Rehoboth Jonker Afrikaner accorded him hospitality and, with supplies replenished, he set off westwards, following the course of the Kuiseb River.

His determination is marked by thin wagon-wheel tracks, still visible to the present day, as they etched their passage on rocky screes, descending the Great Escarpment to the desert. Reaching Walvis Bay in 1837, he entered the history books as leading the first scientific, cross-country expedition to complete this gruelling passage.

Five hundred years following these epic events a new class of explorer crosses the ocean, jetting on airwaves 10 kilometres above a turbulent sea that tossed the stout caravels of Cão.

Reclining in comfort with refreshments and digitised films to absorb their attention, they cover continents in the time it took the wagons and horses to move a few brutal miles.

Their destination is where glossy adverts proclaim Swakopmund… where the Skeleton Coast comes to life…

Skydiving, sand-boarding, quad-biking and seafood restaurants replace jolting wagons, bully beef and exhausting winds.

How many of these modern explorers would be prepared to exchange their comforts for the inconceivable hardships suffered by those resolute rovers of yesteryear? Were it not for them, the Skeleton Coast would not have come to life for us.

This article appeared in the 2009/10 edition of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia.

Hu Berry was a scientist, conservationist and specialist tour guide. He was one of Venture Publications' most valued authors. Sadly he passed away in July 2011. To read more about him click here.