Namibia Tourism Board – looking back on 2012

July 3, 2013Namibia Tourism Board – skill-building for tour guides

July 4, 2013By Steve Felton

To see a lion in the wild is one of the great moments in nature – arguably worth many sightings in national parks, however natural the parks may be. How often have you heard the conversation:

“Been to Etosha.”

“See any lions?”

“Yeah.”

Funnily enough, I had never seen lions in Etosha until I accompanied a group from WWF in Mongolia who were on a study to tour to Namibia to see how conservation works here. We did spot two females in the park. But it was a sighting in the wild, in Kunene, which brought the most satisfaction.

The Mongolian visitors were at Wêreldsend, which had once been the end of the farming world, the last farm before the desert on the road to Torra Bay. Now it is a training centre for IRDNC, Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation, which provides technical support to Namibian communal conservancies.

Top of the list of questions from the Mongolians was: “How do people live with wildlife?” And that’s a tricky one. Although most stock losses in the area are caused by cheetah, lions often get the blame. And to be fair, they also take some cattle. In Kunene, where grass is sparse, especially in a drought year, to lose a cow to lions is a tragedy.

The answer to the question lies in the conservancy system. Members of Torra conservancy benefit from tourism, which generates half of the conservancy income through a joint venture lodge agreement with Wilderness Safaris. Some conservancy members work at Damaraland Camp, and their income spreads throughout their families. The conservancy also assists with payments to farmers who have lost stock.

All very interesting to the Mongolian WWF staff, but their eyes lit up when Russell Vingevold, who runs Wêreldsend, said there was a pride of lions nearby, and would we like to see them?

It was a short hop with a posse of 4x4s to a nearby spring – off the road and known only to the locals. Russell made it plain that the pride was unaccustomed to people, not like the lions in Kenya’s Masai Mara which are regularly encircled by cars with tourists clicking away. We would have to be very cautious.

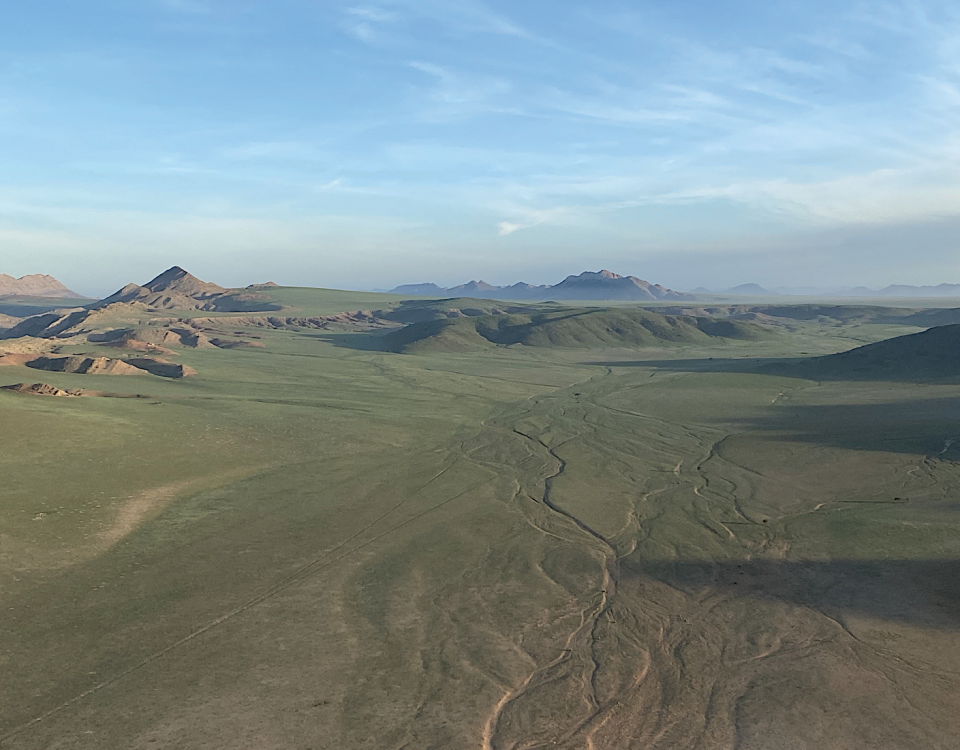

Our three vehicles stopped at some distance from the spring, and with the aid of binoculars a couple of lions came into view, moving along a small river bed. We drove closer, slowly, as quietly as possible, and finally found a spot where we could see some cubs resting under a tree as the sun gradually settled and the earth warmed in the glow.

We kept quiet and still as two females moved across our view with a powerful grace to settle with the cubs. Reaching for a lens I touched the horn with my elbow. BLAAAA. It was an awful moment. But the lions just looked up and then away again. No harm done.

We moved on and around the spring to find a better vantage point, even closer. The pride seemed content. The remains of a zebra lay nearby, and I got my best shot with the mountains in the background.

The lioness in the front is wearing a collar, and is probably Xpl-75, collared by Dr Flip Stander. If I am right, this is the Huab pride and this is what the Desert Lion site has to say:

‘Xpl-75 was born during May 2007 at Swartmodder spring in the Uniab River. Her mother, Xpl-22, separated from the Agab Pride and formed the Obab Pride. Xpl-75 and her siblings were raised in the Obab and Hunkap Rivers. At the age of 2-3 years, Xpl-75 and her sister (Xpl-76) dispersed and settled in the Huab River. A satellite radio collar was fitted to Xpl-75 on 5 Nov 2012.’

It had been a magic moment, but soon the talk came round to the reality for locals. If the drought is bad then the antelopes and zebras will be thinner on the ground. The lions may prey on cattle, turning people against them. Living with wildlife is a constant balancing act. Conservation is bringing income not only from tourism, but also from the sustainable use of wildlife. Torra gets the other half of its income from trophy hunting, the sale of live game, and game meat. The conservation of wildlife means that predators will be out there somewhere.

If you are very lucky you will see them.