Quelea quelea

Visiting Etosha National Park in early May this year we encountered what might be a once-in-a-lifetime experience: watching a flock, or rather flocks, of Red-billed Queleas at Goas waterhole one morning coming in for their daily drink. Apparently this usually happens twice a day, but my fellow waterhole visitors in the car got a bit fed up with the once-in-a-lifetime experience after a few hours and I had to leave the birds on their own for the rest of the day, to my utter dismay.

Text Pompie Burger | Photographs Pompie Burger

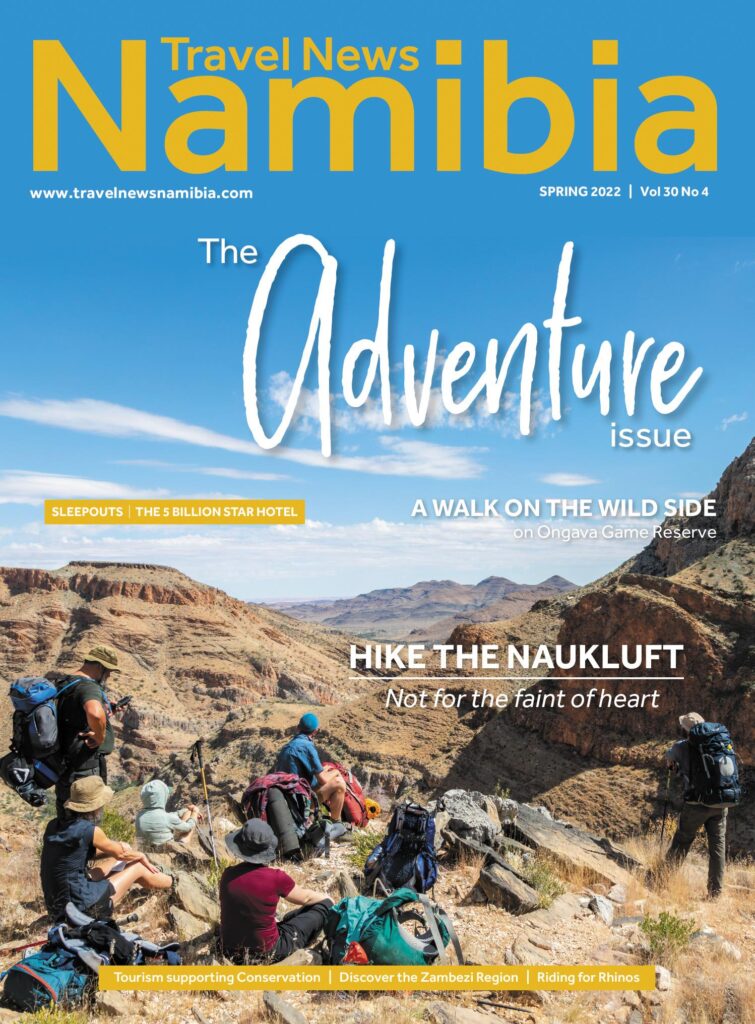

From the Spring 2022 issue

Writing this article I cannot wait to mention their sheer numbers. I counted them and when I came to one million I got a little tired and time was running out, so unfortunately we will have to go again next year. The second fact, which might be slightly more accurate than the first, is that Queleas seem to be the most abundant bird species on earth, and we were lucky enough to see all of them in one morning at Goas waterhole. Apparently there are more than 1.5 billion Queleas in the world, take or leave a few thousand. The bad news is that over a million birds are killed annually, mainly by pesticides in control operations. The other main cause of deaths is food shortage. The fact that pesticides kill so many Queleas in turn leads to killing many of the predators hunting them; especially with large-scale, direct localised use of pesticides.

Apart from pesticides and food shortage their other enemies are birds of prey. Lanner Falcons are the main culprit, which we can confirm. We saw about five Lanners hanging around in nearby trees waiting for the appropriate moment to have another and yet another mid-morning snack. Whether their sheer numbers are of any use to the Queleas to avoid or frighten potential predation is doubtful, because any self- respecting Lanner can just fly into a flock of Queleas with its bill open and fill it to the brim in one go. Other raptors which also enjoy the taste of Queleas are Peregrine Falcons, which are, like Lanners, very agile and fast flying raptors. Also quite fond of this delicacy at waterholes are crocodiles, not present at this particular waterhole, Marabou Storks (present), and Green- backed Herons (absent).

Unfortunately, not only the adult birds are at risk but fledglings and nestlings are also vulnerable, especially to Cattle Egrets and various hornbills like Red-billed, Yellow-billed and Ground Hornbills. Breeding takes place mainly after good rains in early summer (November and December), while in other regions like Namibia, where the rainy season is later, during January and February. As one would expect, breeding is highly gregarious as all of the Queleas’ other activities are. Apparently they are monogamous, but you could have fooled me – who has scientifically monitored that activity? And if so, I am almost 100% sure there are a few males, and females, who do not stick to this very noble rule.

Nests are usually built in trees, with a preference to acacia trees. Fortunately they do not strip the leaves around the nest, but unfortunately at times there are so many birds and nests on a single branch that the branch might break. As for distribution, Queleas occur in sub-Saharan Africa outside the forest zones, thus mainly semi-arid dry thorn veld and grassland. Cultivated land, especially in South Africa, is one of their prime targets, where they can demolish large areas of wheat, sorghum, millet, rice and buckwheat. These are obviously the places where they are most often targeted by control operations.

Moving around in such large numbers – numbers which are especially visible at waterholes – one would expect that all your senses will be attacked, visually obviously, but also acoustically. According to Roberts Birds of Southern Africa the sounds of their different calls are chatter, warbled, tweedle-toodle, chirt and finally their alarm call “chuck”. Luckily our sense of smell was not present, maybe because of the strong wind. Although, being so many birds, I wonder if the wind was possibly something of their own making.

As for their acrobatics, they should always be perfect if you look at the sheer numbers. They have to be exceptionally well-behaved in flight, otherwise the number of head-on collisions would be more than the car accidents during the annual Easter weekend on Namibian roads. In flight they look extremely well coordinated as they move in rolling waves from place to place. They normally move in a large flock with numerous smaller flocks also present, making the sight even more spectacular. One can imagine the havoc that would ensue if one bird should decide to fly in the opposite direction of the flock.

Because of their size, these birds do not eat that much. Their diet consists of seeds, grass, and termites. They also do their daily excretion in gregarious fashion – if you ever wondered where the two hills near Halali Rest Camp come from.

The final bad habit of these little birds is that they tend to visit suburban areas, especially bird feeders in gardens. Once word is out that you have put some seeds out you will soon have a flock of Queleas visiting and demolishing all the food from the feeding table before any other bird. Even the Laughing Doves seem to get out of their way when they arrive in numbers. If you are lucky enough to be one of the chosen few on their visiting lists, do have a look at the many variations in their facial markings. If in doubt about the identification of these birds, just count them – if they are more than a million it must be Queleas. TNN