Emboldened conservation

beyond boundaries

The Namib Tsaris Nature Reserve

The area bordering the Namib-Naukluft National Park in Namibia’s south, which may seem like a wasteland to some, has become synonymous with conservation. Unsuccessful commercial small livestock farms having given way to large tracts of fencless land allowing for the unhindered movement of desert adapted wildlife.

Text Le Roux van Schalkwyk | Photographs Le Roux van Schalkwyk

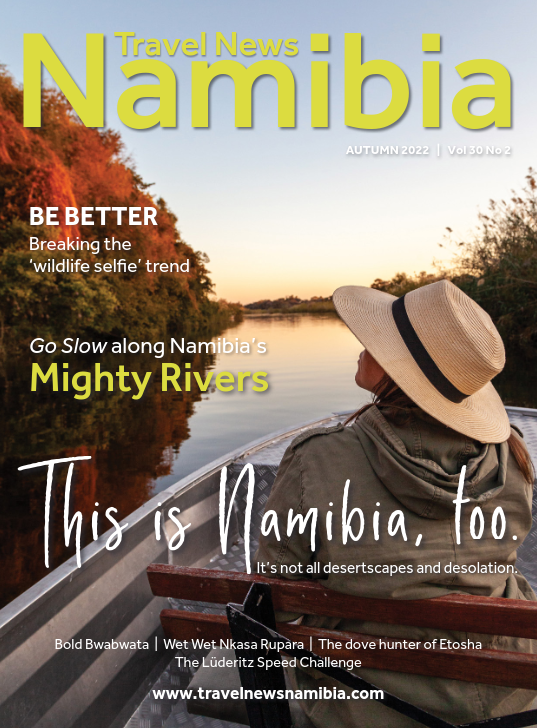

From the Autumn 2022 issue

T he Pro-Namib is a transition zone between the arid Namib and the escarpments to the East where a slightly higher rainfall means a more constant supply of grazing. This region is of critical importance for animals moving out of the desert proper during droughts in search of sustenance. Thanks to various private nature reserves wildlife like gemsbok, springbok and other hardy desert dwellers are able to once again freely follow seasonal migratory routes.

Ondili is not only committed to responsible tourism through a range of low-impact, environmentally friendly establishments situated in some of the country’s most pristine and ecologically sensitive landscapes, but also plays an important role in conserving the Pro-Namib.

NAMIB TSARIS NATURE RESERVE

Although Ondili maintains and develops nature reserves in various parts of Namibia, the group’s most ambitious project is the remarkable Namib Tsaris Nature Reserve. Situated in the ecologically sensitive Greater Sossusvlei-Namib Landscape, the reserve currently covers 120,000 ha.

Namib-Naukluft National Park, with the massive coastal dune belt known as the Namib Sand Sea UNESCO World Heritage Site, forms a large part of this landscape initiative. The private NamibRand Nature Reserve borders on the national park and the Namib Tsaris Nature Reserve also connects to these conservation areas. However, it adds additional biomes to the greater continuous area under conservation. The Nature Reserve includes the Tsaris mountains, characterised by plateaus, gorges and wide-open plains. This means that the vast protected area from the Skeleton Coast to the Sossusvlei dunes, NamibRand and the Nubib mountains now also extends east to the Tsaris mountains and towards the Maltahöhe limestone plateau.

The reserve is made up of farmland previously used for commercial sheep farming but due to the unreliable rainfall in these parts, these farms were never really economically viable. Farmers looking for better land elsewhere and the retirement of the older generation with nobody to take over, have opened opportunities for these farms to be bought over a period of several years and to create larger continuous areas for conservation.

Creating a nature reserve requires various inputs and the following has been done:

REMOVAL OF FARMING INFRASTRUCTURE

Grazing camps are secured with fences that are 1 to 1.2 m high. While necessary when implementing a rotational grazing system on a commercial farm, these fences are detrimental to the natural movement of wildlife. Desert-dwelling animals such as gemsbok are adapted to walking great distances to find grazing and water. This natural movement is hindered by camp and boundary fences as well as causing many fatalities of animals attempting to cross or get through these man-made barriers. Dismantling fences is therefore a vital step in the creation of a nature reserve. Vast unfenced areas with free- roaming wildlife is the aim.

Thousands of kilometres of fencing has been dismantled in the Namib Tsaris Nature Reserve – a job that kept several teams busy for years. Fences can run through gorges which are difficult to access, sometimes up to 10 km away from the nearest farm road. This dismantled material of iron posts and wire had to be carried to the nearest road for removal by truck.

Other deconstruction operations on the reserve included the dismantling of old water reservoirs, drinking troughs, overland water pipes, windpumps, farm buildings and other defunct structures. A further necessary action was excavating the rubbish dumps which developed over decades, containing not only household waste but also hazardous waste and machinery remains.

WATER MANAGEMENT

Naturally, water supply is a vital issue in a desert landscape. Windpumps have been removed and replaced with solar pumps, a much more effective way of controlling how much water is extracted. As wild animals cover longer distances to water points than domestic animals, the number of drinking points in a reserve can be reduced to every 7 to 10 km, depending on the topography and the presence of boreholes. Drinking points have been changed from troughs to sunken drinking holes that are gently sloped and lined with stones to prevent slipping. This way, small animals can access the water and the drinking point can be used to wallow. Where possible, natural springs are integrated into the water supply concept.

RESTORING THE NATURAL BALANCE OF FAUNA AND FLORA

The destructive nature of commercial farming in sensitive areas can have long-lasting effects on the plant- and wildlife.

Overgrazing leads to scrub encroachment. Grass is displaced by bush and at the same time, lack of grass cover causes susceptibility to soil erosion. De-bushing takes place in areas with a conspicuous imbalance in favour of bush. This allows the grass to grow back in certain parts of the reserve.

Hunting played a large role on these farms. Predators were killed because they kill sheep, ungulates because they were useful as a source of meat and because they competed for grazing with the farm animals. In a nature reserve, a balanced variety of species is the aim. Certain animals are actively reintroduced, while some species have returned on their own.

EROSION CONTROL

Due to the aridity of the area, extended periods of drought, overgrazing and tracks laid unwisely are the root cause of soil erosion when it rains. A number of protective measures have been put in place to control this loss of topsoil. This included the construction of small dams to reduce river and stream velocity, as well as building strategically placed drainage channels, setting roads higher than the channel so that water does not run in the road, and building humps to redirect water.

Since these measures have to be carried out in vast areas, it is a costly and lengthy process which needs to be sustained.

Ondili’s commitment embodies promoting nature conservation through its lodges by investing all profits in the establishment and maintenance of the Ondili Nature Reserves. Furthermore, for every guest room at one of the Ondili lodges, Ondili creates at least 1,000 ha of nature reserve in Namibia. The nature reserves in return create jobs for local communities.

When staying at Desert Homestead Lodge and Desert Homestead Outpost, the two lodges situated within the Namib Tsaris Nature Reserve, guests not only get to enjoy the fruits of the ongoing conservation efforts to this incredible area, but also know that their stay contributes to its further development and success. TNN

“For every guest room at one of the Ondili lodges, the Ondili Group creates at least 1,000 ha of nature reserve in Namibia”