The Story Behind Some of Etosha's Special Species

Etosha National Park ranks among Africa’s top game parks and is renowned for its outstanding game viewing. The fascinating stories behind some of Etosha’s game species have, however, disappeared over time. Willie Olivier looks to rediscover some of these stories.

Text & Photographs Willie Olivier

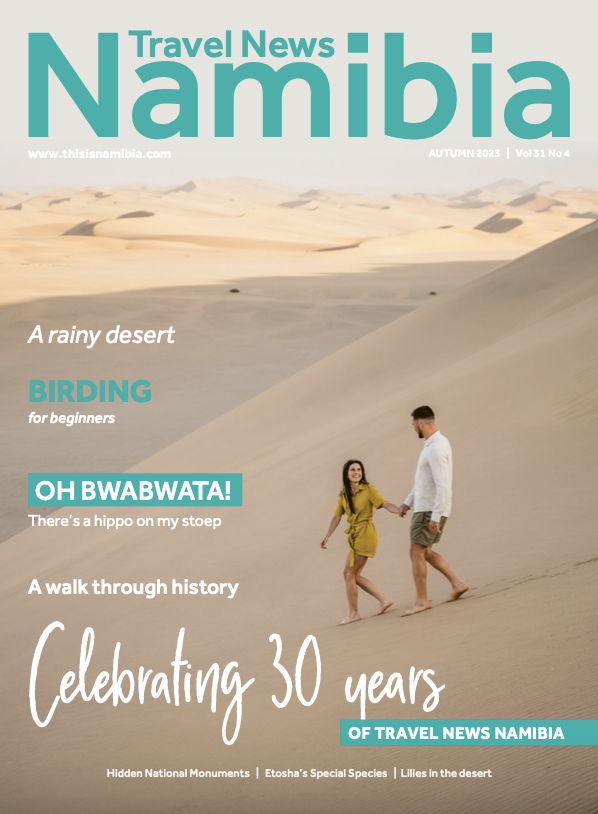

From the Autumn 2023 issue

BLACK-FACED IMPALA

The first animal you are most likely to encounter if you enter through Von Lindequist or Andersson gates is the black-faced impala, which is endemic to northwestern Namibia and southwestern Angola. It is a subspecies of the closely related common impala which occurs further east in Namibia. Its distinctive purplish-black facial blaze extending from the nostrils to the top of the head, the shiny reddish coat and the bushy tail distinguish it from the common impala.

Fearing that the population in Kaokoland would become extinct as a result of a prolonged drought, competition from livestock, poaching and illegal hunting, conservation authorities decided to launch a major capture operation to translocate some of the antelope to Etosha National Park.

Game capture operations were still rudimentary in those days – it was before the use of chemical immobilisation and capture methods such as bomas, drop nets and the use of helicopters, while the rugged mountainous terrain was another major challenge. Thirty-eight animals were captured during the first operation in 1968, which was carried out by blinding the animals with spotlights on dark-moon nights and catching them by the hind legs – no easy task by any stretch of the imagination. Three more groups were captured by using a helicopter to herd them into drop nets in 1969, 1970 and 1971.The animals were transported by road to a game-breeding camp at Otjovasandu in the southwestern corner of Etosha National Park and were later released at Namutoni, Olifantsbad, Halali, Ombika and a few other locations. Interestingly, they have not ventured far away from their initial release sites.

The logistics for one of these operations are simply mind-boggling. Vehicles involved in the operation covered more than 40,000 km during the capture, the transportation of fodder to feed 127 animals while they were quarantined and their translocation to Etosha.

By 1971, a total of 226 black-faced impalas had been translocated to the park. They adapted so well to their new environment that the Nature Conservation Division began selling small groups to game farmers in the 1980s. Despite the sale of the animals and subsequent translocations to communal conservancies, the population in the park currently exceeds 1,500.

BLACK RHINO

Etosha has the largest population of the western subspecies of the black rhino (Diceros

bicornis

bicornis) in the world. The park’s black rhino population was estimated at 55 in the mid-1960s and although this was probably a gross under-estimation, conservation officials were concerned about the survival of the species outside of the park. This motivated the officials to translocate black rhino from Damaraland and Kaokoland to Etosha. Game capture and darting techniques were still rather basic in those days and four of the six rhinos captured in the first operation in 1966 died.

Undeterred by these early setbacks, a total of 43 black rhinos were caught in southern Kaokoland between 1970 and 1972 and only four died as a result of improved drug immobilisation, capture and transportation techniques. A further 21 black rhinos were captured and translocated to Etosha over the next five years, bringing the total number of successful translocations to over 60. The rhinos were released at various locations in the park over the years.

Etosha has played an important role in the re-establishment of the western subspecies of the black rhino population in their former ranges in South Africa. Rhinos from Etosha have been translocated to Augrabies Falls National Park (1985), Vaalbos National Park (1987 – 1990), Karoo National Park (2007) and Addo Elephant National Park (2007).

WHITE RHINO

The white rhino became extinct in Etosha before the end of the 1900s and it was not until 1995 when 10 animals were reintroduced to the park from South Africa’s Kruger National Park in exchange for 30 giraffes. The population was boosted when 12 white rhinos were translocated from Waterberg Plateau Park in the late 1990s, followed by 12 more in 2003.

ROAN ANTELOPE

Although you are not very likely to see roan antelope, except on the off-chance in western Etosha, the park played an important role in the conservation of this charismatic species.

Fearing that their numbers might decrease in their stronghold in Khaudum in the Kavango Region, 74 animals were caught in Khaudum Omuramba in 1970. Transporting them by gravel road over a distance of over 1,000 km – featuring bush tracks negotiable only by four-wheel drive vehicles – was impossible. After a successful experiment to determine the effects of prolonged immobilisation, it was decided to airlift the animals. A 1,8-km-long landing strip was built in the omuramba (an Otjiherero word meaning “poorly defined drainage line”) and the animals were flown in three groups to western Etosha in a C130 Lockheed Hercules air freighter and released in a breeding camp in southwestern Etosha. Operation Roan was not only most likely the costliest short-term game catching operation at the time (R40,000), but probably also the first-ever translocation of such a large group of sedated large ruminants over such a long distance by air – 430 nautical miles.

The population increased rapidly after some animals were released in the west of the park, but they did not adapt well as Etosha lies west of the minimum annual rainfall of 400 mm for roan antelope to establish viable populations. The park, however, provided the founder population of Waterberg Plateau Park when 34 animals were translocated there in 1975. The population increased so well there that surplus animals could later be sold to private game farms in higher rainfall areas.

DAMARA DIK-DIK

The dainty Damara dik-dik is without doubt one of the species most adored by visitors to Etosha, where it occurs naturally. It is one of four African dik-dik species, but the only one occurring in southern Africa as the other three species (Salt’s, Piacentini’s and Guenther’s dik-dik) have limited distributions in east Africa, southern Somalia and the Horn of Africa.

An intriguing fact about the Damara dik-dik is that thousands of kilometres separate the southern African population from the northern population in East Africa where it occurs in southern Somalia, central and southern Kenya and northern and central Tanzania. There it is known as Kirk’s dik-dik, a name honouring the 19th century Scottish naturalist Sir John Kirk – hence the species name kirkii. The first specimen was described from an animal shot in southern Somalia and its generic name, Madoqua, is derived from the Amharic name, medaqqwa, meaning “small antelope”.

It is endemic to southwestern Angola as well as central and northern Namibia with scattered populations further south in suitable habitat. In Etosha, you are almost guaranteed to see them in the Klein Namutoni area, especially along the appropriately named Dik-dik Drive. Early mornings and late afternoons, when they are most active, are the best times to spot them. They occur singly, in pairs or small family groups and although they are mainly browsers, they also eat grasses and herbs in the rainy season.