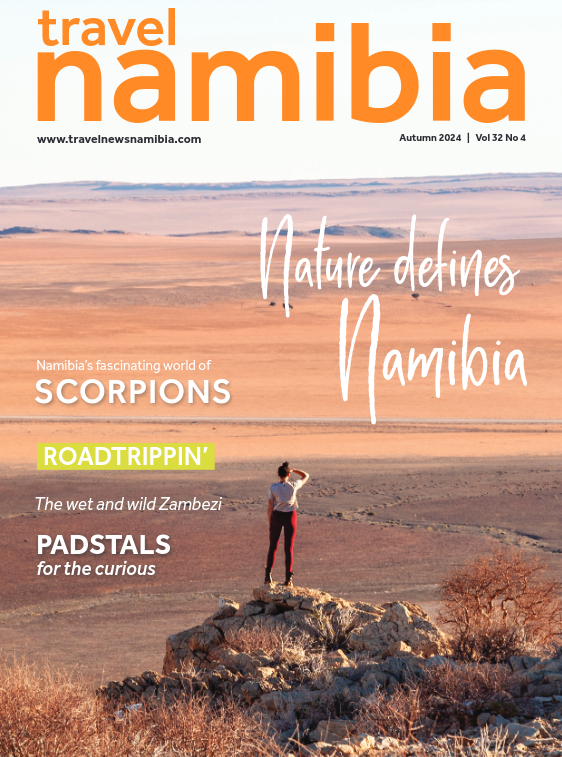

Gardens in

the desert

Transforming a community with a desert-based economy

Text Kirsty Watermeyer | Photographs Kirsty Watermeyer

From the Autumn 2024 issue

Environmental activist Reinhold Mangundu is the project coordinator for RuralRevive. He explains, “We want to create communities where happiness is the indicator for measuring progress. For me, it’s about how we can rethink progress beyond business as usual. We are trying to create environments where people and nature are central to everything because we are inherently a part of nature.”

The desert-based economy that RuralRevive is hoping to build has deep roots in community transformation. Through creating entrepreneurial and employment opportunities and ensuring that there is a linkage with an existing market demand, this project is tackling economic inequality and revitalising the community of Maltahöhe. According to Reinhold, the project also advocates a different way of looking at the responsibility of the tourism sector.

VISITING MALTAHÖHE

We are travelling to the Namib Desert via Maltahöhe. Upon arrival we are greeted with the sight of Blikkiesdorp (which literally translates to Tin Town), the informal settlement on the outskirts of the town. It is easy to notice the social imbalances and desperation that Reinhold told me about. It is estimated that of the nearly 7,000 people that live in Maltahöhe, only 500 people have meaningful employment. The scarcity of opportunities was only exacerbated with the collapse of Karakul sheep farming, leading many to a sense of utter hopelessness.

We are staying at the oldest country hotel in Namibia, the Maltahöhe Hotel, and owner Marika Raves is showing us around. Marika grew up in Maltahöhe and returned as an adult to help save it. She is deeply passionate about the RuralRevive project.

Marika walks us through the RuralRevive campus and explains how the laundry service was the first phase of their project and how it aims to become a laundry services hub for tourism establishments in the ecologically sensitive Namib Desert. They prioritise employment of women from the area, they use solar power and biodegradable washing powders, and their grey water is utilised to feed their vast vegetable garden. “We have our own borehole, where we harvest our water. It goes through the laundry and is then reused in the garden,” explains Marika. It is a far more environmentally friendly approach to cleaning linen than extracting from underground water sources in the Namib Desert, and it is not the only innovative project in Maltahöhe.

Marika explains that the region is dry and the topsoil is not of good quality, therefore they have also launched a project under RuralRevive to manufacture biomass compost. The community harvests plant matter of invasive species to sell back to the project. The harvested plant matter is reduced at the campus woodchipper and added to manure, which they also have in plenty here thanks to the farming community. This process creates compost for their fruit and vegetable enterprises. It is clear that this project has a strong focus on developing possibilities for income sources for the community. “Creating a small-scale economy is vital for a community that was falling apart,” notes Marika.

The campus garden is more than just a supply source for the wider tourism industry operating in the region, it is also a training facility where members of the community are learning the art of horticulture. “This is a place where we test things and teach people how to start from scratch, how to make compost, how to start planting, and more.” Marika explains that through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) they now have a horticultural expert stationed here to assist the community gardeners in real time with their planting, growing and harvesting.

In the future a horticulture academy based in Maltahöhe will form part of the RuralRevive campus. “We want to bring education into this project because that is part of a circular economy. Then at least there is a possibility of training for a school-leaver here. We don’t realise it but sometimes there is no motivation to learn simply because there is nowhere to go and learn,” says Marika.

THE GARDENING REVOLUTION

There is a wave of community and backyard gardeners spreading across the village. So contagious is this movement that even the police station now has their own vegetable garden. Fresh organic produce is creating a localised supply of fresh produce for tourism operations. This in turn means that instead of driving in fresh produce from bigger cities, the tourism industry can buy local, resulting in a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions and fresher produce to serve to guests.

“We’re currently supplying nine lodges but there are more than seventy lodges in the area. Our customers are very happy because something which comes from Maltahöhe is so much fresher, it’s organically produced and it has a story to tell, as it’s from the community. We’ve even had mulberries at the buffet at Wolwedans because you can harvest them, send them and they arrive fresh. The transport doesn’t only have an effect on our carbon footprint and the use of less packaging materials, but it also has a huge impact on the quality served to guests,” explains Marika.

To facilitate convenience for tourism operations, RuralRevive has launched The Barn. According to Marika, lodge managers need a central ordering system that delivers to their doorstep. “This is why we created The Barn, an online store selling produce to the community.”

Marika mentions more exciting phases in the pipeline. These include a recycling plant, which would be a first for the south of Namibia, offering another revenue stream for the community. As Marika notes, “Upcycling suits my community. For the Nama people, it is in their nature to do collection. They will collect bottle tops and make a beautiful flower bed for example.” This creativity is on full show as we drive through Blikkiesdorp, an open-air art gallery of upcycled goods. Trees decorated in would-be trash and artistic entrances to houses instil a sense of pride and beauty despite difficulty.

BEHIND THE SCENES

There are many partners involved in this project, including the Social Security Commission Development Fund and the Julius Baer Foundation, but the Wolwedans Foundation’s “Vision 2030 – The AridEden Project” was the birthplace of RuralRevive.

This project fosters sustainable tourism and conservation based on a business philosophy that balances people, planet and profit. Considering that Maltahöhe is the closest village to Wolwedans and that approximately 20% of their staff come from this community, it is a project that makes sense for business as well as soul satisfaction.

As Reinhold explains, “The foundation is measuring its success based on the progress on the ground. This really is what tourism and conservation should be about. The philosophy of AridEden is happiness for all beings. For me, Vision 2030 is a new narrative about the alternative future that we want to see. A sustainable future.”

SEEING SUSTAINABLE TOURISM IN ACTION

From Maltahöhe we travel to Wolwedans to see how a tourism operation can support a town’s renewal. Wolwedans is the epitome of a classic African safari lodge. It oozes minimal opulence in the desert. Here in this tranquil corner of the NamibRand Nature Reserve we will be treated like royalty. But more than the beautiful surroundings, more than the epic plains cloaked by red sand dunes, more than the welcoming committee or endearing staff, we arrive here with a lingering feeling of authentic environmental consciousness.

Cecilijah Oletu Nghidengwa is the Happiness Coordinator at Wolwedans. On the Heart & Home Tour, she walks us through the workings of everything at Wolwedans, sharing why they put sustainability first. The water, which is believed to have its origins in the Okavango Delta, is pumped from the borehole using solar energy and bottled in glass bottles. Cecilijah points out the many recycling-focused projects here, from laundry bags to plastic bottles and glass that, mixed together, are used to make bricks that build their premises.

“But more than the beautiful surroundings, more than the epic plains cloaked by red sand dunes, more than the welcoming committee or endearing staff, we arrive here with a lingering feeling of authentic environmental consciousness”

Cecilijah walks us through their Desert Academy, their recycling plants, their adopt-a- tree avenue, their repair and maintenance facilities and much more. When asked about RuralRevive, Cecilijah excitedly shares how this project is so important for their vision of sustainability and happiness, and how it is reducing their carbon footprint.

Wolwedans has a purpose which is the pursuit of happiness, and an inspired new way to get there. An ethos that is lived by every member of the team here. Seeing the workings of this lodge and finding out how it is contributing to putting the environment and communities first, makes the whole experience feel more rewarding. Somehow we have renewed eyes to see what an establishment like this in an ecologically sensitive area requires, and could mean to others. We are also aware that for this endeavour to be successful there can be no green sheen, no public relations spin to their story. This has to be authentic.

Cecilijah’s enthusiasm and belief in the better world being created here is infectious. “You’ll see circles everywhere here. It’s our signature, showing our connection to everything and everyone,” says Cecilijah

SOMEWHERE OVER THE RED DUNES

We changed somewhere along the way. Somewhere in between the story of a town and its people transformed and the Wolwedans experience, where we saw first-hand the sustainability-focused operations of this tourism enterprise. Whether it was while walking through the gardens of organic produce or somewhere over the red dunes, something in us felt transformed. It has added a new sense to our experience, the sense of community and consciousness. It somehow even made everything taste better. And believe me the food was already out of this world. But knowing where it comes from, knowing its story, makes it more than the exceptional experience it already was. We feel that we are not just travellers but that through our travel we are contributing to the world we want to see, and this is an added dimension of exploration. This truly is conscious travel, and it feels great. TN