Namib-Skeleton Coast National Park – Namib-Naukluft Park: One of Namibia’s grandest and most complex parks

July 13, 2012Namib-Skeleton Coast National Park – The origins of the extraordinary

July 13, 2012Namibia’s exciting ‘new’ national park – a consolidation of old and recently proclaimed protected areas, is on the cards.

“The proclamation of this protected area represents one of Namibia’s greatest conservation achievements since gaining independence in 1990, and one of the most exciting developments in the history of conservation in this country.” – Peter Tarr

By Peter Tarr, Southern African Institute of Environmental Assessment

It has provisionally been called the Namib–Skeleton Coast National Park, because both the Namib and the Skeleton Coast are already well known, not only in conservation and tourism circles but worldwide, and the brand is regarded as strong by existing and potential new investors. An official name will be announced soon, after more consultation and consideration.

The repackaged park stretches along the entire Namibian coastline, a distance of about 1 570 km, from the Orange River in the south to the Kunene River in the north (Figure 1). It comprises four main terrestrial Management Areas, the Sperrgebiet (name under review) in the south, the Namib-Naukluft, the Central Area and the Skeleton Coast.

In addition, the Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources recently obtained Cabinet approval to proclaim Namibia’s first Marine Protected Area, immediately adjacent to the Sperrgebiet and Namib-Naukluft Management Areas. At its narrowest point in the Skeleton Coast, the park extends about 25 km inland, while at its widest in the Naukluft area it extends inland about 180 km to the top of the escarpment. Namibia is the only continental country in the world that will have its entire coastline protected as a national park.

Eighth largest in world

The new park will be the 8th largest protected area in the world, the 6th largest terrestrial protected area globally and the largest park in Africa (see Table 1), covering an area of 10.754 million hectares, or 107 540 km2.

However, the Namib-Skeleton Coast National Park will not exist in isolation. In the south across the Orange River it borders on the Richtersveld in South Africa, which comprises a protected area of about 160 000 ha within a multiple-use buffer zone of about 398 425 ha. This whole area forms the Ai-Ais/Richtersveld Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA) under a formal co-operative agreement between the governments of Namibia and South Africa.

To the north across the Kunene River it joins the Iona National Park in Angola, which covers about 585 000 ha. The governments of Namibia and Angola have signed an agreement to promote transfrontier co-operation between these parks.

In Namibia the park is contiguous with a large number of protected areas, concessions, conservancies and private land managed for conservation. The extent of land under conservation, particularly private land, is constantly changing (increasing) and that, because there is no registration mechanism for private protected areas and game farms, the sizes below represent an absolute minimum area.

Contiguous conservation areas with the Namib-Skeleton Coast National Park are the Richtersveld and buffer area/communal (RSA Parks), South Africa (558 425 ha); Iona National Park/state, Angola (585 000 ha); and in Namibia communal conservancies (6 235 500 ha), wildlife and tourism concessions (800 000 ha), freehold conservancies and private protected areas (2 050 000 ha), state parks (Ministry of Environment and Tourism) (2 651 200 ha) and the Marine Protected Area (Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources) (1 200 000 ha). Most notable in Namibia are the following:

- Coastal and Marine Protected Area off the Sperrgebiet and Namib-Naukluft areas, running for 400 km up the coast and about 30 km wide, covering an area of 1.2 million ha and containing all Namibia’s islands;

- Ai-Ais/Fish River Canyon National Park, which in turn borders on private protected areas;

- Contiguous with 20 communal conservancies and three wildlife and tourism concession areas, and via them linked to the Etosha National Park (2.29 million ha) and thence to further communal and private conservation areas;

- Borders on at least two million ha of freehold conservancies and private protected areas.

Table 1: The 10 largest protected areas in the world.

| No | Name | Ecosystem | Country | Size (ha) |

| 1 | Greenland’s National Park | Terrestrial and coastal; arctic island | Greenland | 97 200 000 |

| 2 | Ar-Rub’al-Khali Wildlife Management Area | Terrestrial; desert | Saudi Arabia | 64 000 000 |

| 3 | Great Barrier Reef

Marine Park |

Marine and coastal | Australia | 34 500 000 |

| 4 | North-western Hawaiian Islands’ Coral Reef

Ecosystem Reserve |

Marine and coastal | USA | 34 000 000 |

| 5 | Amazonia Forest Reserve | Terrestrial; tropical rain forest | Colombia | 32 000 000 |

| 6 | Qiang Tang Nature

Reserve |

Terrestrial; alpine Tibetan plateau grasslands | China | 25 000 000 |

| 7 | Cape Churchill Wildlife Management Area | Terrestrial; intertidal and marine | Canada | 14 000 000 |

| 8 | Namib-Skeleton Coast National Park | Terrestrial & coastal; desert ecosystems | Namibia | 10 754 000 |

| 9 | Northern Wildlife

Management Zone |

Terrestrial; desert | Saudi Arabia | 10 000 000 |

| 10 | Alto Orinoco-Casiquiare Biosphere Reserve | Terrestrial; tropical rain forest | Venezuela and Bolivia | 8 000 000 |

Greatest conservation achievement since independence

In total the ‘new’ park borders onto over 14 million ha of land and sea that is managed primarily for wildlife, biodiversity, conservation and tourism. Together this represents a contiguous area of almost 25 million ha.

One of the greatest challenges with potentially the greatest rewards is to develop effective, constructive and efficient co-management mechanisms across these land- and seascapes to optimise both the environmental (including biodiversity) and socioeconomic values, while at the same time using these open systems to (a) allow the historic movement and migration patterns of wildlife in response to the highly variable climatic conditions to become re-established, (b) mitigate and buffer the impacts of climate change and thereby make the area more resilient to change, and (c) create incentives for neighbouring landowners and custodians to become part of this conservation landscape, thereby further strengthening the contributions of the area to socioeconomic development and environmental conservation.

The proclamation of this protected area represents one of Namibia’s greatest conservation achievements since gaining independence in 1990, and one of the most exciting developments in the history of conservation in this country.

The park occupies the most arid lands in Africa south of the Sahara. Apart from the eastern edge of the Naukluft, the whole park falls below the 100 mm median annual rainfall isohyet with over 60% of the land area of the park falling below the 50 mm isohyet. In addition to the extremely low annual rainfall, it is also hugely variable with an annual coefficient of variation ranging typically from 80% to over 100%.

With its high evaporation rates and low rainfall, the park experiences an average water deficit of about 2 metres per year. In the north and central areas rain falls mainly in January to March, while in the Sperrgebiet rainfall is about equally unlikely in all months of the year. The fact that some rain falls in the winter months, derived from frontal weather passing the Cape, results in the succulent vegetation of this area.

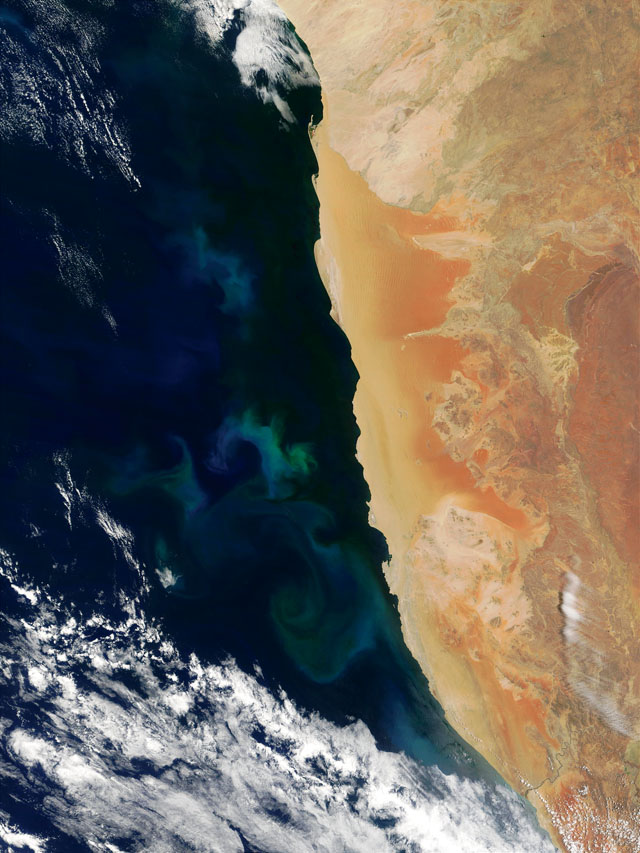

The climate of the park is influenced mainly by the cold Benguela Current and the South Atlantic Anticyclone. Temperatures are generally moderate (average minimum and maximum temperatures during the coldest and hottest months respectively reflecting a range of about 7–32˚C), fog is frequent (about 125 days per year on the coast dropping to about 40 days per year 80 km inland) and wind is a dominant feature.

The southern part of the coast is a particularly high wind-energy area, especially in the summer months, with average daily speeds of over 40 km/h. These winds are mainly from the south and drive the Benguela Current northwards, carry sand from the shore into the adjacent land, particularly into the southern dune fields, and cause upwellings along the coast, which bring nutrient-rich water to the surface.

It is important to understand why the Namib is a desert. First, the cold waters of the Benguela Current cool the air so much that it cannot rise up and develop into large rain-bearing clouds. The sea air remains trapped in a layer from the sea to about 600 metres above sea level.

Moisture from the sea is seen only as low clouds and fog. Second, moist tropical air from the east and north has usually shed its moisture before reaching the Namib coastal areas. And even when rain-bearing clouds do approach, they are usually blocked by breezes from the sea that blow inland for some distance, often to the escarpment. And finally, any moist tropical air blowing towards the desert descends over the escarpment, warming and drying out as it sinks down. These factors all combine to make rainfall an unusual event in the Namib.

Table 2: Percentage of each biome contained within the park and within immediately contiguous conservation areas.

| Biome | NSCNP | Communal

conservancies |

Concessions | Freehold land | Other state parks | Total |

| Namib Desert | 76 | 14 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 95 |

| Nama Karoo | 3 | 13 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 23 |

| Succulent Karoo | 85 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 91 |

| Coastal | 99 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 99 |

Global biodiversity

The new park covers the coastal biome and three terrestrial biomes, namely the hyper-arid Namib Desert, the Nama Karoo and the Succulent Karoo. The amount of each of these terrestrial biomes protected by the park is shown in Table 2. These biomes contain a number of different vegetation types and an even greater number of habitats.

The geology of the park ranges from the oldest rocks known, the Vioolsdrift Gra-nite Suite and the Haib Group (2 600––1 650 million years old) in the south of the Sperrgebiet, to the youngest geology comprising the Namib Sands (70 million years old to present) which dominate the central Namib sand sea and large parts of the Sperrgebiet.

The park contains a large number of globally significant features. The following are perhaps the most notable:

- A global biodiversity hotspot comprising the Sperrgebiet, the most diverse desert in the world. Nearly 25% of Namibia’s plant species (over 1 050) occur here, on less than 3% of its land surface, many of them endemic to the area and highly range restricted.

- Three Ramsar sites, being Walvis Bay, Sandwich Harbour and the Orange River Mouth, this last being a joint site between Namibia and South Africa.

- Eight Important Bird Areas (IBA), being the Kunene River Mouth, Cape Cross Lagoon, Namib-Naukluft Park, Mile 4 Saltworks, 30 km beach (Walvis Bay to Swakopmund), Walvis Bay, Sandwich Harbour and the Sperrgebiet. In addition, there are four IBAs covering islands immediately off the Namib-Naukluft and Sperrgebiet Areas and within the Marine Protected Area, namely Mercury Island, Ichaboe Island, Lüderitz Bay Islands and Possession Island.

- Two Important Plant Areas (IPA), being the lichen fields in the Central Coastal Area and the Sperrgebiet. Additional IPAs occur immediately to the east of the Sperrgebiet and contiguous with it, and linking it to the Ai-Ais/Huns Mountains/Fish River Canyon complex, and to the east of the Skeleton Coast Area and northern parts of the Central Coastal Area, incorporating the entire northern escarpment zone and linking to the Etosha- National Park.

- All the IPAs and IBAs also qualify as Key Biodiversity Areas, sites of global significance for biodiversity conservation, and using globally standard criteria and thresholds.

- The only two perennial rivers crossing the Namib form the northern (Kunene River) and southern (Orange-Gariep-Senqu River) borders of the park respectively. In addition, 12 significant ephemeral river systems drain westwards across the park. Of these, the flows of two rivers are stopped by the Namib Sand Sea, forming pans surrounded by sand dunes (Tsondabvlei and Sossusvlei).

- The park contains a huge diversity of desert landscapes and scenery, habitats, biodiversity and, despite its fragility, a large number of economic opportunities if carefully planned and managed. The Northern Namib comprises large mountainous areas with incised river systems that support some of Africa’s most charismatic megafauna such as desert-adapted elephants, rhino, giraffe, lion, leopard and cheetah, made all the more remarkable by their presence in this hyper-arid zone and desert scenery. The Central Namib contains huge vistas over mainly gravel plains with inselbergs that support arid-adapted plains game such as gemsbok, springbok and ostrich.

- The Southern Namib contains Namibia’s sand sea, an area of some four million hectares of sand dunes and ridges, giving way to the escarpment in the east and some of the most dramatic scenery at Sossusvlei and in the Naukluft. And finally, the Sperrgebiet, with its 100-year history of diamond mining and closure to the public-, with rich archaeological, palaeontological, historic and biodiversity values and a dramatic coastline. This diversity offers huge potential for tourism routes from the south to the north, within Namibia’s desert biomes, both within and adjacent to the park.

- Contiguous with the south-eastern point of the Sperrgebiet is the Ai-Ais National Park, which contains the Fish River Canyon, the second-largest canyon in the world after the Grand Canyon in the USA.

- The western border of the park is on the coast, 25% of which is designated as Namibia’s first coastal and marine park. This enigmatic and poignant coast – the Coast of Skeletons – contains many shipwrecks, the bones of early mariners as well as those of whales and seals.

- The park’s northern border is shared with the Iona National Park in Angola, while areas on its southern border in South Africa are being developed under conservancy type approaches. The western border of the park is shared with communal lands (about 54%), freehold lands (about 45%) and the Ai-Ais National Park (<1%). Almost 100% of the park’s border with communal lands comprises conservancies and wildlife and tourism concessions. At least 60% of the freehold bordering land comprises private parks and land managed for wildlife and tourism. This means that over 80% of the park’s western border is shared with neighbours practising land uses that are both friendly and compatible to that of the park. This offers huge opportunities for partnership and co-management.

With these and many other attributes of the park and its adjacent areas, serious consideration should be given to seeking World Heritage Site status for the entire region (the park and selected adjacent areas).

This would hugely increase its marketability, its ability to generate socioeconomic benefits and also assist with its management, without forfeiting any of the options that are currently, or may in future, become available.

This article appeared in the 2009/10 edition of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia.

2 Comments

How do I get a reliable and affordable tour company that can provide me with a quote to tour the skeleton coast.

May you send me a quote for Namib dessert experience to included:

1. Pick up from Windhoek International airport 30th May 2019 at 11:30 am. Drop off to the Windhoek International airport. 2nd June 2019

2. Accomodation

3. Camel ride tour of dessert sand dunes

4. Quad Biking

5. Sand boarding

Hi Allan,

Thank you for your comment. Please follow this link for our list of tour companies in Namibia that we recommend and contact them directly: https://www.travelnewsnamibia.com/plan-your-trip/tours/