Namibia: Kameldorn Garten and Restaurant

November 19, 2012Rain 2012: Pitter patter, here and there

November 19, 2012By Helge Denker

KAZA is about the size of Sweden, covering around 440 000 square kilometres. It embraces national parks, game reserves, forest reserves, community conservancies and wildlife management areas.

Altogether, there are over 50 protected areas within KAZA. It encompasses most of the Okavango River and Upper Zambezi River basins, includes the Okavango Delta and the Victoria Falls, and spans five Southern African countries – Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

It is a real ‘big-picture’ vision of conservation across boundaries.

The signed treaty and the lines drawn on a map have not really changed realities on the ground in the five countries. Here, the people live on a mixture of subsistence agriculture, livestock herding, fishing and a little bit of tourism. Wild animals try to follow ancient migration routes, often passing through communal farmland.

This creates a variety of issues that need to be addressed before the KAZA vision can be realised.

This creates a variety of issues that need to be addressed before the KAZA vision can be realised.

A central objective of this vision is to ‘enhance the sustainable use of natural and cultural heritage resources to improve the livelihoods of local communities within and around the KAZA TFCA and thus contribute to poverty reduction’.

Direct benefits flowing from conservation to local communities highlight a paradigm shift of recent decades, which has significantly increased the viability of many state-run and community conservation areas in Southern Africa. At the KAZA scale, improving livelihoods requires that wildlife movements, human wildlife interactions and human-wildlife conflict receive close attention.

On a map, the extent of KAZA, the apparent wildlife movement the area enables, and the number of rural communities it embraces certainly look impressive.

But the map does not necessarily reveal barriers and threats that can severely restrict wildlife movements, which in turn results in heightened localised pressure and related human-wildlife conflict. This threatens the long-term effectiveness and success of KAZA.

Tangible community benefits from wildlife generally depend on finding a healthy balance between wildlife and subsistence agriculture. Within KAZA, this can be achieved if wildlife can follow its seasonal migration routes without being forced into unhealthy proximity to farming activities and settlement.

The tourism value of communal areas is enhanced through the effective zoning of wildlife corridors. This allows communities to diversify their livelihoods by supplementing agriculture with tourism income. By keeping migration routes open, local wildlife pressure is reduced and the overall health of wildlife populations is maintained.

The tourism value of communal areas is enhanced through the effective zoning of wildlife corridors. This allows communities to diversify their livelihoods by supplementing agriculture with tourism income. By keeping migration routes open, local wildlife pressure is reduced and the overall health of wildlife populations is maintained.

All of this equates directly with the second key objective of KAZA, which is ‘to promote and facilitate the development of a complementary network of protected areas… linked through corridors to safeguard the welfare and continued existence of migratory wildlife species’.

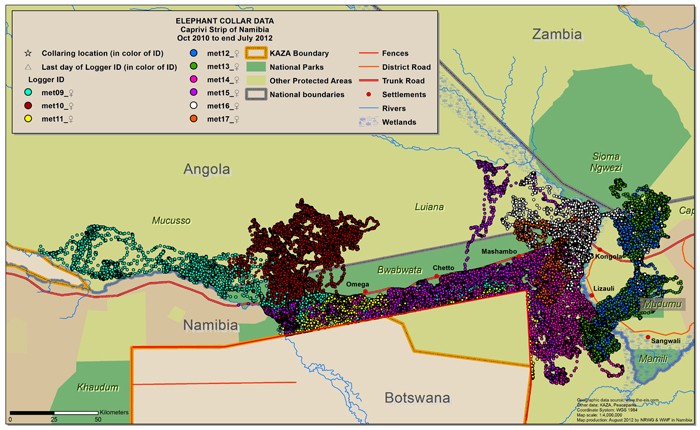

Several years of wildlife monitoring in various KAZA countries illustrates high-pressure zones created through migration bottlenecks and movement barriers such as fences and human activity.

Scientists from the Ministry of Environment and Tourism in Namibia have been working with WWF scientists to collect a wealth of data, and have recently begun to collaborate and share information with their Botswana counterparts to understand wildlife dynamics better at regional level.

Scientists from the Ministry of Environment and Tourism in Namibia have been working with WWF scientists to collect a wealth of data, and have recently begun to collaborate and share information with their Botswana counterparts to understand wildlife dynamics better at regional level.

The FENCES project – a very apt acronym for Facilitating Environmental Connectivity of Ecosystems and Species – is an emerging regional partnership that seeks to foster connectivity and freedom of wildlife movement by applying the valuable information being collected.

Freedom of wildlife movement across the Caprivi is vital in relieving elephant pressure in both Namibia and Botswana, by allowing the animals to move north into Angola and Zambia.

KAZA is home to the largest contiguous elephant population in all of Africa, estimated at around 250 000.

The border fence between Botswana and Namibia, internal fences in Botswana, and settlement and human activity along the Trans-Caprivi Highway in Namibia, are all creating movement barriers for elephants, buffalos and other wildlife.

The border fence between Botswana and Namibia, internal fences in Botswana, and settlement and human activity along the Trans-Caprivi Highway in Namibia, are all creating movement barriers for elephants, buffalos and other wildlife.

The African wild dog, one of the continent’s most endangered predators, is another highly mobile species that needs the freedom of movement that only an area the size of KAZA can provide.

A recent meeting held in Namibia, attended by species experts from all KAZA countries, laid the foundation for improved conservation of the canid.

Farming is a vital component of the rural livelihoods and economies of all KAZA countries, yet a more strategic approach to fencing, agricultural activities and wildlife management can facilitate free wildlife movement without threatening farming activities.

And local communities are able to integrate wildlife and agricultural land uses when the economic, social and ecological benefits of conservation outweigh the costs of living with wildlife. The large rivers within KAZA are primary focus areas for conservation and wildlife-based tourism, as are human settlement and agriculture. These may appear to be incompatible, yet effective land-use zoning can allow different uses to be integrated and to co-exist, thereby providing significant benefits to all sectors.

This potential can be realised only through active collaboration amongst the five countries, as well as among the different protected areas and resident communities at a more localised level.

There needs to be collaboration among the different land-use sectors. Success requires ongoing consideration of wildlife dynamics to be able to address and overcome threats and barriers. And it requires the political will to ensure free wildlife movement and maximum wildlife benefits for local communities. Through this, the area can become just as impressive in the field as it currently is on a map.

This article was originally published in the November 2012 edition of Flamingo magazine.

All photos courtesy of WWF Namibia.