Save the Rhino Trust: Their passion lives on

July 6, 2012Stories in stone: Namibia’s true national archives

July 6, 2012By Dr Philip “Flip” Stander, Kunene Lion Project

The image of a lion walking along an isolated beach has captured the imagination of filmmakers, scientists, and wildlife enthusiasts around the world.

It is a phenomenon that, today, occurs only along Namibia’s northern coastline. The Skeleton Coast lions became famous in the late 1980s, when wildlife film producers such as National Geographic released remarkable images of lions on the beach, captured primarily by the legendary wildlife filmmakers, Des and Jen Bartlett.

Dedicated nature conservators in the Skeleton Coast Park monitored the lions regularly, and the old Department of Nature Conservation supported a rudimentary research project on the lions. Although funding and resources were limited, they radio-collared five lions and collected a fair amount of data on their movements and ecology.

The coastal lions of the 1980s maintained a stable presence in the Skeleton Coast Park. They hunted and fed on the available prey, such as seals, beached whales and gemsbok, and they were breeding successfully. These individuals illustrated remarkable adaptations to the unique and extreme ecological conditions.

However, the bordering land-use practices at the time were not conducive to wildlife conservation, and especially not to lions. The Namibian tourism industry was just cutting its teeth, and community-based conservation was a foreign concept. In an area with tremendously high tourism value, local communities living just outside the narrow Skeleton Coast Park (±30 km wide) were attempting to survive from uneconomical livestock farming. Conflict between the lions and livestock farmers was inevitable.

Lions raided their livestock and local communities retaliated by shooting and poisoning them. By the end of 1990 all the known and radio-collared lions had been killed. In retrospect, and with the wisdom of time (and CBNRM), it was a sad state of affairs. Killing lions was then the only available option, but only to protect an uneconomical and unsustainable livelihood in an area with very high tourism potential.

Ten years later the Kunene Lion Project was launched under the guidance of the Ministry of Environment and Tourism. Lions had not been observed in the Skeleton Coast Park since the 1990 conflicts, but signs had been recorded further inland.

More importantly, however, was the tremendous growth of the tourism industry, and the emergence of communal conservancies where local people gained ownership over their wildlife and derived direct benefits, such as tourism-related levies. The environment for wildlife conservation, and for lions in particular, had changed considerably since the late 1980s, and it was time to revisit the lion conservation problem.

The Kunene Lion Project was initiated in 1998 with an intensive burst of systematic research and monitoring. One year into the study, 20 lions had been radio-collared. Marked individuals were tracked from the air over vast distances, and on the ground over arduous terrain. Monitoring was focused on the individual lion, and its social interactions or associations with other lions. We collected data on births, cub survival, deaths, immigration, dispersal, and movements.

The efforts soon produced exciting results and the data showed that lionesses gave birth to large litters (mean average: 2.8) and that cub survival was high (91%). In addition, cubs became independent early, and the interval between litters was shorter than elsewhere in Africa.

These dynamics allowed the population to grow rapidly. The annual rate of increase was over 25% in 1999, 2000 and 2003. On average, the Kunene population increased at a rate of 19% per year.

With the increase in numbers one could predict that the lion population would need to expand its range. In doing so, some lions will eventually find their way to the coast and, if food resources are adequate, establish themselves there.

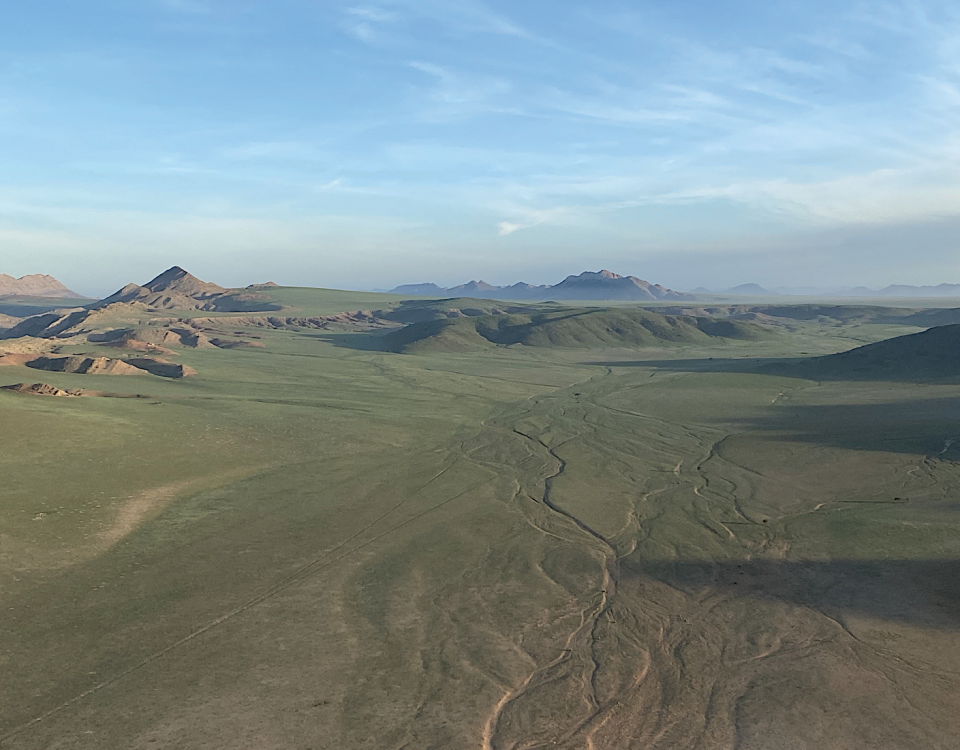

The results of our research on their movements and dispersal from 2002 to 2005 show that this prediction is quite accurate. In 2000 the Kunene lion population lived in an area of only 4 260 km2. Between 2000 and 2004, this area increased in size, by a factor of 6.7, and measured 28 880 km2 in January 2005. Individual lions, and small groups, dispersing from their natal home ranges to occupy new habitats, marked this expansion.

The most interesting and significant dispersal came from a small group of four young lions (a female, named Xpl-10, and three males) that had moved to the Hoarusib River course. They were born at Aub Canyon, near Palmwag, in September 1998.

At the young age of 14 months, along with six other siblings, they broke away from their pride. At 20 months, Xpl-10 and the three males separated from their siblings and moved, first to the Hoanib River and subsequently settling in the Hoarusib River more than 130 km to the north.

In July 2001 they killed some cattle and a few donkeys at Purros. Due to the progress in community-based conservation, and the efforts of the local tourism concessionaire, the Purros community agreed that we should capture the lions and relocate them back in the Skeleton Coast Park. Much had changed since the late 1980s. The following night, with the help of Wilderness Safaris, we darted and moved the lions back into the park. The translocation was successful, and the immediate human-lion conflict was resolved.

The lions remained in the Hoarusib River course, and as time went by ventured ever closer to the coast. In March 2002, Xpl-10 gave birth to two cubs in a rocky outcrop less than 5 km from the beach. Born and raised in the coastal area, it was not a surprise when we eventually found the cubs on the beach in August 2002. From the known records, this sighting marked the return of lions to the coast after an absence of 12–13 years. By October 2003 the two cubs had grown large enough to be radio-collared, and we darted them on the beach, at the mouth of the Hoarusib River.

A few months later, in April 2004, Xpl-10 produced her second litter. On this occasion the litter was born in the reeds, at the mouth of the Hoarusib River. With her two sub-adult daughters and two small cubs in tow, Xpl-10 remained in that area throughout 2004. Moving back and forth along the river, they spent a substantial amount of time on the coast. Xpl-10 can be seen as the founding lioness of a new era of Skeleton Coast lions. She has produced and successfully raised two litters of cubs on the coast, and has seen to it that they are suitably skilled and adapted for survival along Namibia’s forbidding Skeleton Coast.

This article appeared in the 2005/6 edition of Conservation and the Environment in Namibia.