Namibia wetlands: Awareness campaign launched

February 11, 2013Namib Naukluft Lodge & Soft Adventure Camp

February 12, 2013By Bill Torbitt

Miscellaneous facts on the Namibian Environment

Why Dead Vlei is dead

Nearly a thousand years ago, the Tsauchab River, which used to feed the vlei as well as the better-known Sossusvlei, diverted its course, leaving Dead Vlei literally high and dry.

The once fairly plentiful water supply that fed the camel-thorn trees growing in the pan ceased, the clay floor of the vlei set like a sheet of concrete, and the trees died and dried out.

The vlei is not entirely dead though – some small plants survive from the moisture carried in by morning mist. Be aware that when you are posing for a photograph sitting on one of the grey dead branches, that it is older than nearly all the existing buildings in Europe.

What causes fairy circles?

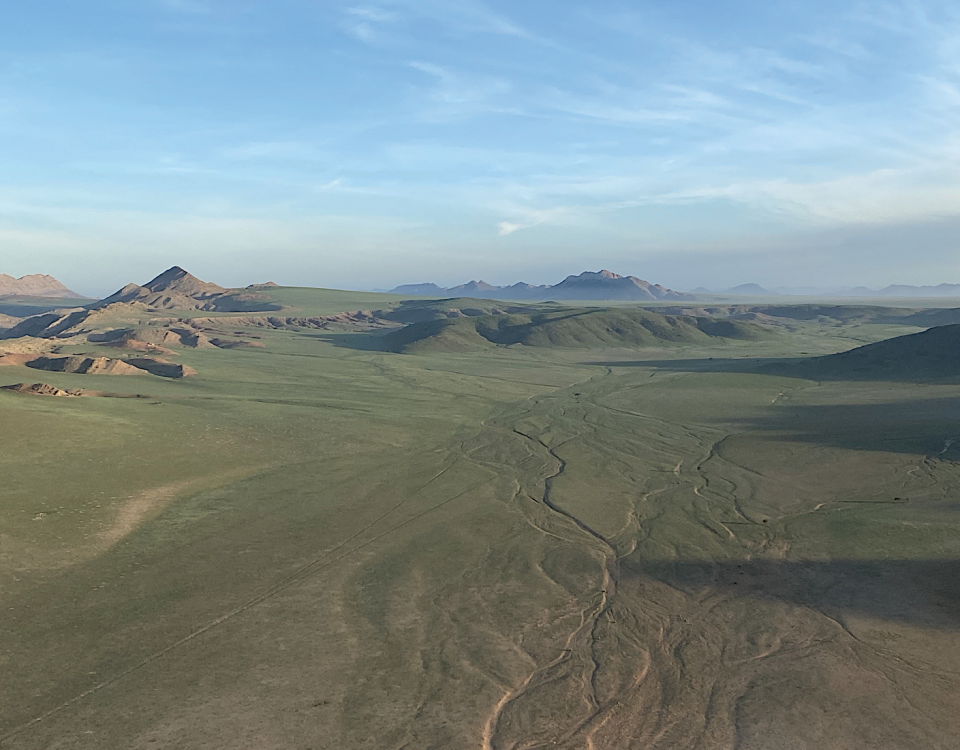

Fairy circles are strange barren circular patches, found on the arid grassy plains of Namibia.

They are the subject of much superstition and many legends, but obviously, due to their almost perfect circular symmetry, they must be caused by some toxin or growth-inhibitor emanating from the centre of the circle.

This is supported by the fact that the circle can grow in extent and then ‘die’, with the bare patch filling once again with grass growth, when the toxin is presumably neutralised. However, some circles persist for many years. The nature of the anti-growth agent or toxin remains unknown. Perhaps, for the sake of tourism, it is better to stick with the legends.

How the aardvark, aardwolf, anteater and armadillo differ?

As animals they are totally unrelated, but they have in common a diet almost exclusively of ants or termites.

Perhaps by convergent evolution they all have long sticky tongues for sucking up insects. An aardvark is the sole representative of the order Tubulidentata.

Despite its Afrikaans name, it is unrelated to pigs, regardless of its vaguely pig-like snout and ears. The name of the order refers to its unique hexagonal tube-like teeth, which grow continually throughout its lifetime. An aardvark can dig into a termite’s nest at great speed, and with its tongue can devour tens of thousands of ants or termites at a sitting.

An aardwolf is also not a wolf – it belongs to the hyaena family, albeit in a subfamily all of its own. It is a shy nocturnal creature that also devours vast numbers of termites every day. It poses no threat to farmers or to their livestock.

Anteaters are related to sloths and do not occur in Africa – they are New World animals, as are armadillos. However, the unrelated scaly anteater or pangolin occurs widely throughout Africa and Asia, including Namibia. They too form a ‘stand-alone’ biological family – the Manidae. They are unusual mammals, as they are covered with keratin scales, resembling ‘walking pine cones’. They do not have teeth, but dig into termite nests with their powerful front claws. They are endangered to some extent, being hunted for their meat, and also because they are in demand in Asia for their ‘medicinal’ properties.

That elephants don’t get drunk?

At least not from eating fermenting marula fruit, a legend probably promoted by the manufacturers of the popular liqueur.

Elephants prefer their marulas fresh.

However, they are not necessarily teetotallers – a herd of Asian elephants once got at the rice-wine stock of an Indian village, then went on the rampage and killed several of the unfortunate villagers.

That trees defend themselves against being eaten by giraffes?

You may think that giraffes have a unique advantage in being able to reach the juicy upper leaves of acacia trees. Good news, except for the tree. However, the trees can defend themselves by infusing their foliage with a chemical that gives it a bitter taste, and they can even ‘warn’ other trees to do the same by releasing a wind-borne chemical message!

Sources and references available from bill@iway.na