The Nama Padloper Route

April 4, 2013Did you know? – Miscellaneous facts on Africa

April 4, 2013Text and photographs by Jana-Mari Smith

As tough as a rhino hide, the Namibian trackers of the Save the Rhino Trust (SRT) are the often-overlooked heroes of the conservation success story that is ensuring the survival of the desert-adapted black rhino (Diceros bicornis bicornis) in Namibia.

The immense efforts of the past three decades – the SRT in cooperation with Government and local and international partners – has achieved what was once thought nigh impossible: transforming a population that was a breath away from extinction into the largest free-roaming black-rhino population in the world. And since the late 90s, the population has been steadily increasing.

Behind this success story, which has received global recognition and acclaim, are the men and women who spend up to three weeks at a stretch in the field to keep a watchful eye on this ancient species. They collect data, monitor the health of these hardy pachyderms and in general deter would-be poachers by their mere presence.

Their job is integral to the success of rhino preservation in Namibia. And their job, in a nutshell, is one of the toughest there is.

These intrepid custodians of this treasured endangered species are able to survive in one of the most inhospitable terrains in Southern Africa for weeks on end. They embody an endeavour that makes them essential to rhino conservation efforts.

These Sherlock Holmes’s of rhino tracking underpin the mission of the SRT to monitor and protect the desert-adapted black rhino in Namibia’s remote north-western Kunene Region. Teams are delegated to monitor specific zones within the 25 000-square-kilometre core rhino area – by vehicle or on foot. A specialised team is equipped with donkeys and camels, which can easily traverse terrain not accessible by vehicle.

“Manfred Uiseb and his colleagues have come to identify with conservation, and have become natural custodians of the desert-adapted black rhino.”

In March it was my privilege and once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to join a rhino patrol in the company of three other visitors.

The mountainous terrain of Damaraland, strewn precariously with ochre-coloured rocks of all shapes and sizes, and intersected with deep gullies, dry riverbeds and steep canyons, is difficult to describe to anyone who has not yet traversed it on foot.

There is no such thing as a flat surface in this terrain. From the moment the trackers step down from the vehicle, they demonstrate their remarkable expertise in navigating the area. From my wobbling vantage point far behind them, they seemed to glide across the landscape, avoiding both living and non-living obstacles in their path with ease.

We had left the SRT base camp, Mai Go Ha, at 06:30. A mere two hours later one of the eagle-eyed trackers, 24-year-old Manfred Uiseb, spotted a rhino in the distance.

While we, the visitors, were still orienting ourselves, Manfred and his colleagues, Abner Naseb (30) and Justus Hendricks (44) had already assembled the necessary equipment and were making their way swiftly towards the rhino – ‘the hippo of the land’, as they jokingly describe this prehistoric mammal.

“My association with these animals is personal. I feel they are my rhinos, almost as if they were my pets. They are as important to us as our cattle.”

Through their jobs, these three men and the other local trackers have come to identify with the cause of rhino conservation, and have become natural ambassadors for the desert-adapted black rhino.

“The rhino is a wonderful animal,” says Manfred. “This job is important. The role we play is important in the community, because we know the rhino and can teach our people,” Manfred explains. “My association with these animals is personal. I feel they are my rhinos, almost as if they were my pets. They are as important to us as our cattle.”

When I finally reach the three men, they are collecting data. We are standing 150 metres away from this critically endangered mammoth, a living fossil and an integral part of the landscape. Despite its enormous size – grown males can weigh over 1 000 kilograms – the rhino is moving fast along the ridge of the mountain. It looks tiny against the looming accumulation of basaltic rock.

A grey ghost, whose two horns – the unfortunate source of all its troubles – stand out white against its grey hide. Apparently our rhino had taken a mud bath in the not-so-distant past.

The haste of the trackers was understandable. They knew that these bulky animals were deceptively nimble and fast. Once they sensed a human presence, they could vanish in a flash. The trackers had only a minute or two to record the details before the rhino would vanish around the curve of the mountain.

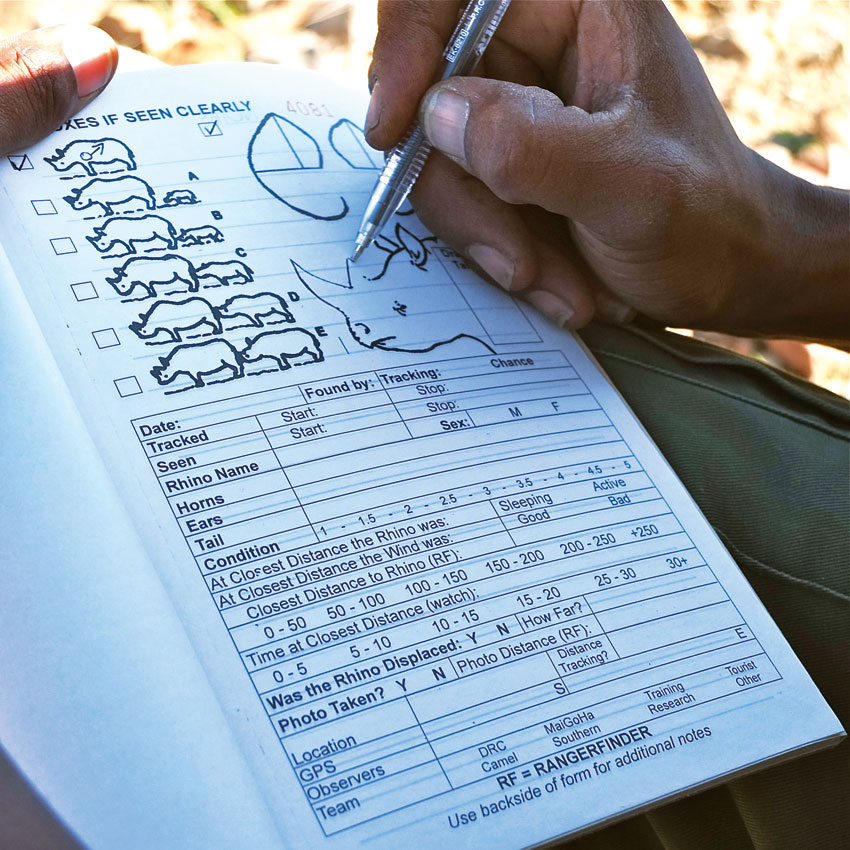

Typically, each team of trackers consists of four members. Each one fulfils a specific task, such as ticking off items on the rhino-sighting form, taking photographs, noting GPS coordinates, and so on.

Despite these challenges, the men are proud of what they do, and are not planning any career changes soon.

While out on their patrols, which take 15 to 18 days at a stretch, the trackers rise in the early morning. They convene at the nearest water source, mostly a natural spring, to scout for fresh signs of rhino.

As a rhino’s home range can extend over 80 to 120 kilometres, the trackers face a host of challenges, including searing heat, long distances, rough terrain, skittish animals and above all, the dangers posed by wildlife.

As rhinos do not comprehend the hard work these men are doing on their behalf, it is not surprising that there are regular accounts of rhino charges. Moreover, this wilderness terrain is not home only to rhinos. Elephant, lion, cheetah, hyaena and leopard roam the landscape, and are not too pleased when they encounter a group of humans.

Among the many stories told by the trackers are those of life-saving strategies such as jumping into the centre of a favourite rhino snack – the poisonous Euphorbia damarana bush, ubiquitous in this area – to escape a close encounter with one of these precious pachyderms. Trees, which are in short supply and tend to be flimsy in this remote habitat, have nevertheless served as useful high perches to evade a snarling pack of lions.

Despite these challenges, the men are proud of what they do, and are not planning any career changes soon.

Abner, who has worked as a tracker for the SRT for the past decade, says that one of the most vital tools of his trade is being able to read spoor and interpret nature in general. Successful rhino tracking depends on being able to tell how fresh or old a spoor is. This is a skill he and most of the trackers learnt as young children. “We are spoor children. Reading footprints is a natural part of growing up here, as most of us come from farming families.”

A subtle shift in a rock, a graze of a hoof, a half-chewed leaf, is all it takes to get the day going for these men.

Justus says the work as a tracker has taught him many other skills into the bargain. These include working with tourists and reading equipment such as GPS devices and range finders. Through the SRT, all the trackers have attended various workshops and courses.

But they don’t deny that their job is tough.

“We go where the rhinos go. In the old days, they were easier to reach. Now, with increasing populations and tourists, they move ever deeper into the bush. It is frustrating and makes our jobs harder.”

The men all agree that “This is not a job for everyone. It’s partly secret work. You must have honour.”

Help conserve the black rhino

While the rhino population in Namibia is steadily increasing and being protected, the situation remains fragile. The Save the Rhino Trust depends on funding to continue its work.

Due to cost cutting the world over, funding is becoming scarcer, yet ever more critical. Rhino poaching has exploded in neighbouring countries such as South Africa and now more than ever, the critically endangered desert-adapted rhino needs the help of the public.

In the event of the SRT closing its doors due to lack of funding, there is no doubt that poaching in Namibia will resume and escalate, and the safety of the black rhino will deteriorate sharply and rapidly.

The SRT is grateful for any donation, however big or small.

For further information, contact the SRT at www.savetherhinotrust.org or email [email protected].na

This article was originally published in the April 2013 Flamingo magazine.

1 Comment

These trackers are SO amazing! I applaud them and give them all my respect for doing what they do and being examples for not just Namibians, but for people all over the world. I hope Manfred, Justis and Abner will read this and know how much they are appreciated!