ROCKING

DAMARALAND

A Journey Through Namibia's Geological Wonders

I love rock formations. Perhaps inherited from or spurred on by my mother, who would pick up pebbles and stones wherever we went on family trips through Namibia. From an early age, I was encouraged to peer tentatively at the ground or marvel at mountains. High school geography wasn’t all it cracked up to be, I didn’t become a geologist. Every road would have led me to this eventuality, writing a love letter to Damaraland and her rocks.

Text Charene Labuschagne | Photographs Le Roux van Schalkwyk

From the Winter 2024 issue

But you don’t have to be a rock person to love Damaraland. The rocks grow on you, whether you like it or not. Long before you see the first mopane tree – the most abundant source of green in this landscape – Damaraland begins to unfold. Driving northwest from Omaruru, the escarpment gradually drops. Through dips and turns, cascading hills and a meandering road through them, the snug valleys eventually give way to a rewarding expanse, dotted with granite mountains in the distance and mopane savannah all around. If it weren’t for the beautiful stretch of road, and a village at the base of the mountain, you could easily mistake it for a dystopian sci-fi movie set. It’s precisely the opposite. A very real utopia.

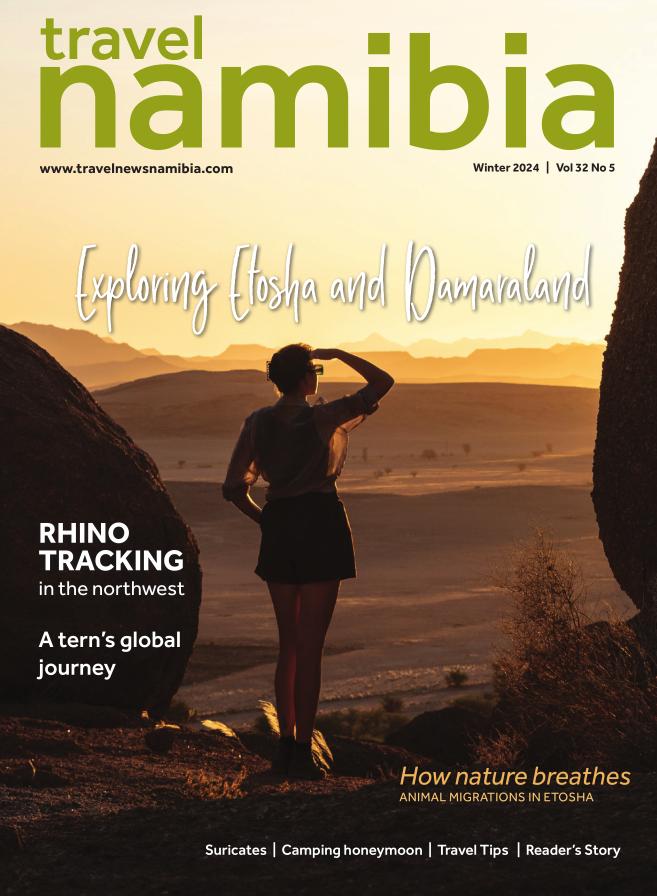

Frantically, I grab my phone and try to capture this cinematic masterpiece. It was at this moment, at the very beginning of our trip, that I realised the pictures might not do this place justice. It beckons, with a luring gesture, to be felt and lived.

Our sojourn for the next few days, Twyfelfontein Adventure Camp, lies at the base of a monolithic granite mountain. The raised platform tents are positioned, facing another nearby mass of rock, looking like a big chunk of ginger snap cookie, with crumbs scattered around. As we clamber up the camp’s staircase to the sunset spot, I’m forced to hold on to the railing for balance. My head tilted back, from side to side, just admiring the rocks. How aeons of heat and cold, wind and dust chip layers and boulders off the old block, forming smooth- looking edges and concaves. Yet you graze a naked elbow against them, and it’s rough as sandpaper. Specks of rock, clustered together. And then you look up, over the lookout, where Damaraland’s flat top mountains create a play of gradients on the horizon and two mountain zebras frolic on the plain, kicking up dust in the golden hour light. Gin and tonic in hand, with the strong southwesterly wind breezing, I’m buckled up for lots more of this.

TWYFELFONTEIN ROCK ENGRAVINGS

Damaraland’s biggest drawcard for visitors is the Twyfelfontein rock engravings, the largest accumulation of ancient engravings on the African continent, and Namibia’s first World Heritage Site. Situated at the foot of yet another granite mountain, a short walk with a local guide takes us to its base. Along the way, we stop at the derelict homestead of David Levin, who bought the land in 1948 and attempted to farm livestock.

My mind painted pictures of the Levin family and their home on the doorstep of an estimated 5000 rock engravings. Imagine the children playing in this ancient, spiritual place, where shamanistic rituals are said to have taken place centuries ago. Sympathising with his wife, as she was surely just as doubtful of the viability of the nearby spring, as David. Giving it its name Twyfelfontein – doubtful fountain.

While their farming efforts could not withstand the harsh climate and scarce water, the majestic engravings must have kept them here longer than anticipated, as if the Levins knew they struck metaphorical gold. The land was just never supposed to be used for farming.

The local Damara people had long kept their distance from the site, considering it to be a wildly spiritual place, likened to a grave. And spiritual it is, even centuries later, on a guided tour. Etched into the granite are seemingly endless depictions of wildlife, what is assumed to be a map to waterholes in the broader area, and a few unexpected animals in between, including a seal and other abstract engravings of multiple- headed giraffe and a lion with a hand at the end of its tail. When touring the Twyfelfontein rock engravings, perhaps the best part of the adventure, besides getting to be in the midst of ancient ritual land, is peering beyond the tour trails. When you look around, as I do, marvelling at the rocks themselves, evermore engravings unveil themselves. A lone rhino etched into a flat, sloping boulder, with the mountain filling in the background, a giraffe here and a zebra there.

After our tour, we take some time to read the history and significance of the site in the visitors centre. The San bushmen shamans are said to have created the engravings, slowly chipping tiny parts of the rock, forming braille textured artworks. This process of repetitive tapping and intense concentration would then spiral into a shamanistic, lucid dream, where they connected with the spirit of the land and its animals, most often in an attempt to conjure rain or other favourable conditions.

With this in mind, viewing these engravings becomes meditative too, considering every sharp tool’s hammer hit against the granite and imagining San bushmen travelling incredible distances, coming across this library in the rocks.

ORGAN PIPES

After paying our dues, the guide on duty gestures towards a small canyon, explaining the way to the Organ Pipes. This would be a self-guided tour, we figured. Down the gently sloping river bank, we approached the organ pipes from downstream, upwards. I like to think this is the best route, as the geological phenomenon unfolds slowly, then all at once. Again, the photos that preclude this visit only sufficed in making me wonder why it’s an attraction. You just have to be there.

Initially leaning sideways, these tiers of rectangular rock splinters gradually stand upright, as you come around a bend in the canyon. Surrounded on both sides by walls of intricately placed, or periodically chopped cascades of dark rust rock, this unassuming sight, which takes only a quick stop to visit, caught me off guard. I could easily have a picnic under the nearby mopane tree and spend the afternoon amongst these brutalist mini cathedrals.

The result of the intrusion of liquid lava into a slate rock formation, these columnar basalts which resemble the long and symmetrical look of organ pipes were formed about 150 million years ago. Gradually exposed to erosion, one can only imagine what still lies hidden under the soil of this ancient land.

ABA-HUAB RIVER AND THE DESERT-ADAPTED ELEPHANTS

As the name suggests, Twyfelfontein Adventure Camp had an expedition up their sleeves. And considering that Damaraland is ephemeral river territory, this adventure would take us up the Aba- huab in search of the desert-adapted elephants. Now, I am no stranger to elephants and their shenanigans. Across the country, if you don’t happen to spot the large mammal, their markings in the bushveld – trees shredded to smithereens or completely uprooted – indicate their presence. Fascinating about their desert-adapted cousins, besides the ability to venture long distances with very little water, is the fact that they refrain from damaging the flora.

What a curious juxtaposition, these giants treading softly in thick river sand, so gently going about picking greenery from trees. They say an elephant never forgets. It appears the desert-adapted ones make this sacrosanct, preserving their habitat for the next time they venture along this route. There isn’t much to go around in this desolate place, and so, the large wrinkly-skinned animals, who seem so out of place here, are one of Damaraland’s great custodians for forestation and sustainability.

In low-range gear, kicking up dust as we drive through the river, its high basalt banks form steep, rock shoulders to the Aba-huab. Around a densely shrubbed bend, and there they are. Roughly 16 elephants browsing, with two little ones bringing extra entertainment value. As they venture further downstream, our guide maintains a safe following distance, and we periodically stop as the giants in our company go for a dust bath, and the babies comedically try to keep up while learning the limits of their limbs.

This year’s rainy season has been less fruitful than hoped for. The few drops that fell have formed small ponds along the banks of the Aba- huab. Here, at the swampy water’s edge, we spotted Grey Heron, Hammerkop and Abdim’s Stork, the latter two being my first sighting of the birds. We had found the elephants and gotten so much more than bargained for, with a delightful tick of the twitcher’s list.

PETRIFIED FOREST

Our rendezvous through Damaraland took us back in the direction of Khorixas, where another delightfully meandering road weaves through the burnt orange landscape. Soon every second kilometre had a roadside, DIY sign exclaiming “PETRIFIED FOREST AND WELWITSCHIAS!” Himba and Damara craft stalls also dot the roadside. Sometimes it might not look like anybody is there, but pull over your vehicle and a friendly face will pop up to help. While we were tempted to check out one of the unofficial petrified forests, it being my first time, we decided to stick with the official one.

My mind played many tricks on me when picturing the petrified forest. This brings me back to the time my German exchange student stood stunned in the Quiver Tree Forest, eventually daring to ask where said forest was. While the Petrified Forest is a large accumulation of pine trees turned to rock, coming from a European country with traditional pine or oak forests, it’s best that you do not imagine a forest at all.

Arriving in the area over 260 million years ago by a great flood, these large tree trunks lay half exposed by millennia of erosion. Buried under the sand, the wood was deprived of oxygen and silicic acids broke down the particles. Quartz particles replaced that of the wood, forming incredibly preserved growing rings, nodes and bark that turned to stone. The largest single trunk is a whopping 45 metres long and satiated my appetite for mind- boggling rock formations.

BEYOND LIFE ON MARS

Leaving the red hues of Twyfelfontein and its surrounds in our dust, the Damaraland expedition ventured a little further inland. Flat-top mountains are the hallmark of this area, I think as we approach Grootberg. Through the mopane savannah, the monolithic mass emerges. At the nape of a picturesque pass that ventures further to the Palmwag area, a steep jeep track climbs the Grootberg mountainside. Once on the plateau, it’s hard to believe this is a mountain. As far as the eye can see in all directions, Grootberg stretches out wide to a blood-curdling drop beyond view. An entire ecosystem exists on top of this great expanse.

I like to think Namibians have certain je ne sais quoi for picking the best spots. Whether driving an endless dirt road and knowing just which tree to stop at for a sandwich and coffee, venturing up a river and locating the perfect rock overhang for a campsite, but especially when it comes to positioning lodges. Grootberg Lodge is a testament to that.

Walking through the reception corridor, a sneak peek of the view gestures you towards the deck where the main landing of Grootberg Lodge sits perched on the edge of a magnificent valley. Grootberg, as the name suggests, is a big mountain, and its namesake lodge is located at one of its funnels. From here, ever more flat-top mountains colour the horizon, and the breathtaking valley below, its massive scale and meandering water table tributaries leave me wondering how much life exists here, that we cannot see with the naked eye.

A sunset drive takes us across the plateau, where springbok and zebra graze unbothered as saturated rain clouds billow above. I notice the rocks, of course, which lie scattered next to the game-viewing vehicle. Solid, tan-coloured clusters with a multitude of tiny holes withered away. Our guide’s response to my inquiry on the natural phenomenon puts a smile on my face. “That’s just nature,” he says. And this is the gaze from which any non-geologist can appreciate rocks. It’s fascinating how they might be formed. As in the case of these hollowed rocks, a softer matter was wedged into the mix, eroding at a quicker pace than the hard sediment around it. But “it’s just nature” is often clarifying enough.

The drive concludes at a scenic lookout point, where a gin and tonic is poured and savoured as the sun sets behind a distant mist bank. Never have I felt so compelled to yell with childlike excitement “I’m on top of the world!” With another steep descent down Grootberg’s edge at our feet, the Torra conservancy cascades before us with ridged mountains and great expanses, in the picturesque light of sunset and the added tonality of rain clouds.

Another meandering road leads through this landscape, down the Grootberg Pass and into the hinterland. Tomorrow we will take this road that demands to be driven at a leisurely pace. For the moment, all the woes of a fast-paced life reach a screeching halt. All that matters are the rock formations that insist on being marvelled at. The gin and tonics insist on being ice cold. And the views – be they a small mountain lookout like at Twyfelfontein Adventure Camp, or one of grand scale like at Grootberg – that insist on leaving your soul stirred and humbled by the majesty of nature. TN