Slofari

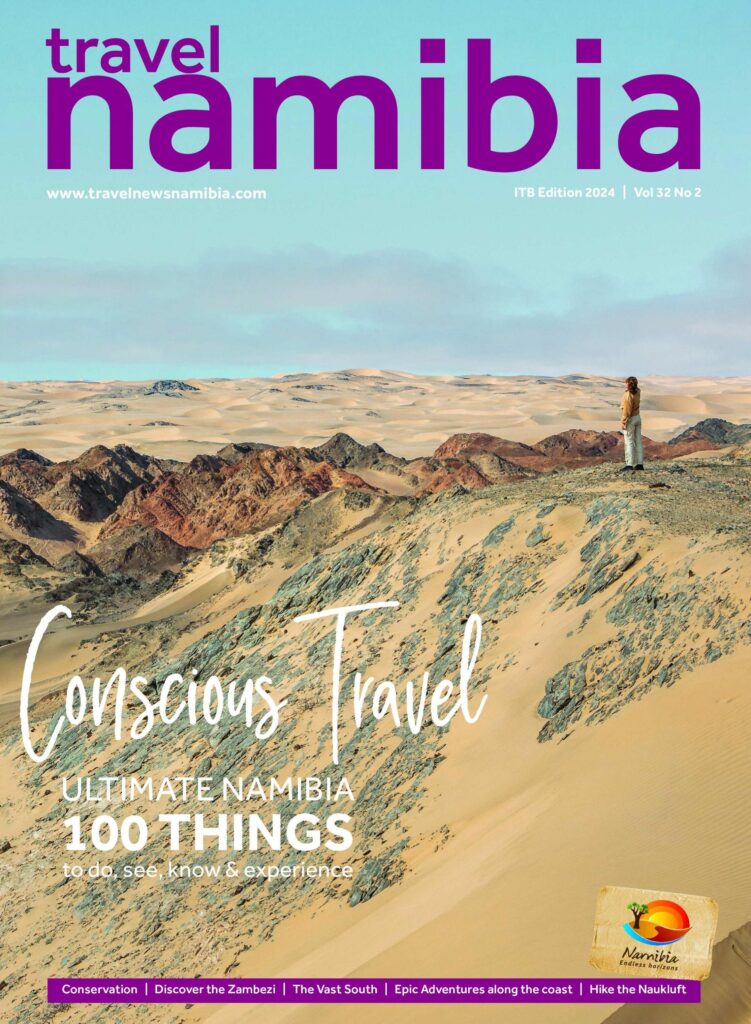

Namibia allows you the time to s-l-o-w down

Not only is slow travel witnessing a global resurgence, but it is also encouraging more meaning ful exploration that promotes ecotourism and conservation projects, writes Iga Motylska after visiting seven of Namibia’s conservancies.

Text Iga Motylska | Photographs Iga Motylska

From the ITB 2024 issue

While you won’t find the word “slofari” in the Oxford Dictionary just yet – give it a few years – the colloquial portmanteau between the words “slow” and “safari” speaks to the growing trend of taking one’s time to travel more meaningfully and with purpose, in stark contrast to the travel-till-you-drop mentality of mass tourism.

Slow travel is a mindful approach of taking the time to see less, but experience more. It is about exploring one or two regions rather than sprinting through an entire country merely to tick the boxes. Slow travel is about immersing yourself within a culture to better understand its people and their way of life. It is about partaking in authentic, community-led experiences with those who have the best interests of the environment at heart.

Since the world re-opened, slow travel is witnessing a resurgence, even more so among visitors returning to a country or destination for a second or third time. While in the past, slow travel was most popular among more mature travellers, who often have more time and money at their disposal, these days it is becoming increasingly popular among younger, environmentally conscious generations, and even those who lead digital nomad lifestyles.

In some ways, technology has helped to slow down the manner in which we travel. Many professionals no longer need to be in the office to work, giving them more time at their destination. And while the irony of sporadically logging in to work from their holiday destination is not lost on remote workers, not having to return in a hurry to their workplace after a two-week vacation actually affords them more time to truly immerse themselves.

DELIGHTFULLY LONG DISTANCES

Namibia is a slow destination by design. Its raw landscape lends itself to turning down the dial on our internal speedometers and turning up the radio. This is mostly due to Namibia’s far-stretching distances, where the average speed limit is restricted by dirt roads and free-roaming wildlife – much to travellers’ delight.

Be sure to add more time to your travel plans when packing for this land of endless horizons. Because while private charters and fly-in safari circuits are becoming increasingly popular for those who can afford it, a large part of the average traveller’s experience is about how far the road stretches until it disappears. Part of the adventure is road tripping to the country’s most remote areas and savouring it for as long as possible.

CONSERVANCIES AND CONCESSIONS

Namibia has long been a global pioneer of responsible travel which champions slow travel. It was the first country in the world to design its post-liberation constitution around conservation, the protection of its land and the responsible management of natural resources. 1996 saw the introduction of communal conservancies – self-governing entities that are managed and operated by members of their communities. Their emphasis is on socio-economic development and long-term sustainability in the form of partnerships between communities and the government, as well as the private sector.

Today, more than a fifth of the country, or 824,093 km², is made up of communal conservancies that comprise 86 partner communities with 244,587 members and 42 lodges as a joint venture between private lodge operators and communities. About one in ten Namibians, particularly those living in remote areas, is involved in the ecotourism sector. These communal conservancies inspire Namibians to be stewards of the land and custodians of their future, while creating socio-economic value, promoting employment opportunities and offering skills training.

Many joint-venture eco-lodges are in hard-to-reach locations, beyond the usual jaunts of the in-and-out traveller. They are constructed in a low-impact manner using natural materials and are built off-the-grid – partially due to the lack of electricity infrastructure.

Their remoteness lends itself to a digital detox (some deliberately do not have WiFi) and curated wellness packages such as breath work, yoga, meditation and spa treatments. Slow-paced activities may include San walking safaris for a better understanding of their innate connection with Mother Nature, stargazing, or visits to partner communities, non- profit projects and conservation programmes.

Namibia allows you the time to slow down, if only you’ll let it, while nurturing community-driven conservation projects for long-term sustainability.

RECOMMENDED CONSERVANCIES:

- Twyfelfontein (Camp Kipwe)

- Skeleton Coast Park (Shipwreck Lodge)

- Torra (Damaraland Camp)

- Wuparo (Nkasa Lupala Tented Lodge)

- Kabulabula (Serondela Lodge)

- Kasika and Kabulabula (Zambezi Queen)

CONSERVANCY CASE STUDY: BLACK RHINOS AT PALMWAG CONCESSION

The 580,000-hectare Palmwag Concession in a remote part of north-west Namibia protects one of the world’s largest free- roaming populations of the critically endangered black rhino. This is made possible through the partnership between the Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism, Save the Rhino Trust Namibia (SRT), Wilderness and the Gondwana Collection, alongside three community conservancies, namely Sesfontein, Anabeb and Torra.

The SRT-Wilderness partnership within the Palmwag Concession sees Desert Rhino Camp act as a monitoring outpost for one of their tracking teams, while covering the operational costs. This has enabled SRT to increase its monitoring range by 20%.

Visitors to the camp can accompany SRT rangers, in convoy with their Wilderness guide, as they monitor these desert- adapted rhinos. They submit data – on population numbers, geographic distribution, human-wildlife conflict and human- induced disturbances – to the largest, longest-running black rhino database in the world.

Findings from a six-year study published in Frontiers in January 2023, titled From seeing to saving: How rhinoceros-based tourism in north-west Namibia strengthens local stewardship to help combat illegal hunting, outlines how this partnership has bolstered local-level stewardship and improved conservation outcomes for the population.

In this way, rhinos are actively protected by the communities living in the protected areas bordering the Palmwag Concession. The case study states that between 2012 and 2018, there has been a 200% increase in tourists – the majority of whom embrace a slow-travel and eco-conscious ethos. This has generated US$1 million for the three conservancies during this time and has seen a 340% increase in the employment of rhino rangers, alongside a reduction in poaching and illegal hunting. According to the study, “[A] strong positive relationship between community institutions that directly provide support to and benefit financially from tourism with the level of their reinvestment in rhinoceros conservation suggests that communities that benefited more from rhinoceros-based tourism demonstrated higher levels of stewardship.”

“[This] offers evidence and lessons that illustrate how carefully curated wildlife tourism that is designed specifically with community engagement and empowerment in mind may serve as a strong basis for enhanced local stewardship that helps improve wildlife and local human communities,” the study concludes. It is an on-the-ground example of the immense socio-economic and conservation value that conservancy partnerships, joint-venture ecotourism and mindful slow travellers contribute. TNN

HOW TO PLAN A SLOFARI IN NAMIBIA?

- Go with the mindset that less is more.

- Save enough leave days so that you don’t feel rushed.

- Do your research or speak to an expert to plan your time and itinerary wisely.

- Choose responsible tourism providers, such as conservancies, tourism concessions, community- owned tourism projects, conservation-led projects, joint ventures and sustainable establishments with Eco Awards Desert Flower Certificates. Find out more: www.nacso.org.na/conservancies and ecoawards-namibia.org.

- Give yourself enough time. Spend a week or two exploring one region and its surroundings.

- Do a road trip for more flexibility and the chance to experience the landscape from up close. Remember that distances as shown on GPSs are not an accurate indication of travel time.

More to explore

Discover Airlines launches a new direct flight between Windhoek and Munich