THE ETOSHA PAN

an eagle’s eye perspective

Text Anja Denker | Photographs Anja Denker

From the Summer 2024/25 issue

The Etosha pan is a large endorheic basin, covering an area of approximately 4760 km2 and stretching some 120km from east to west and 55km north to south. This area is so vast that it is visible from space.

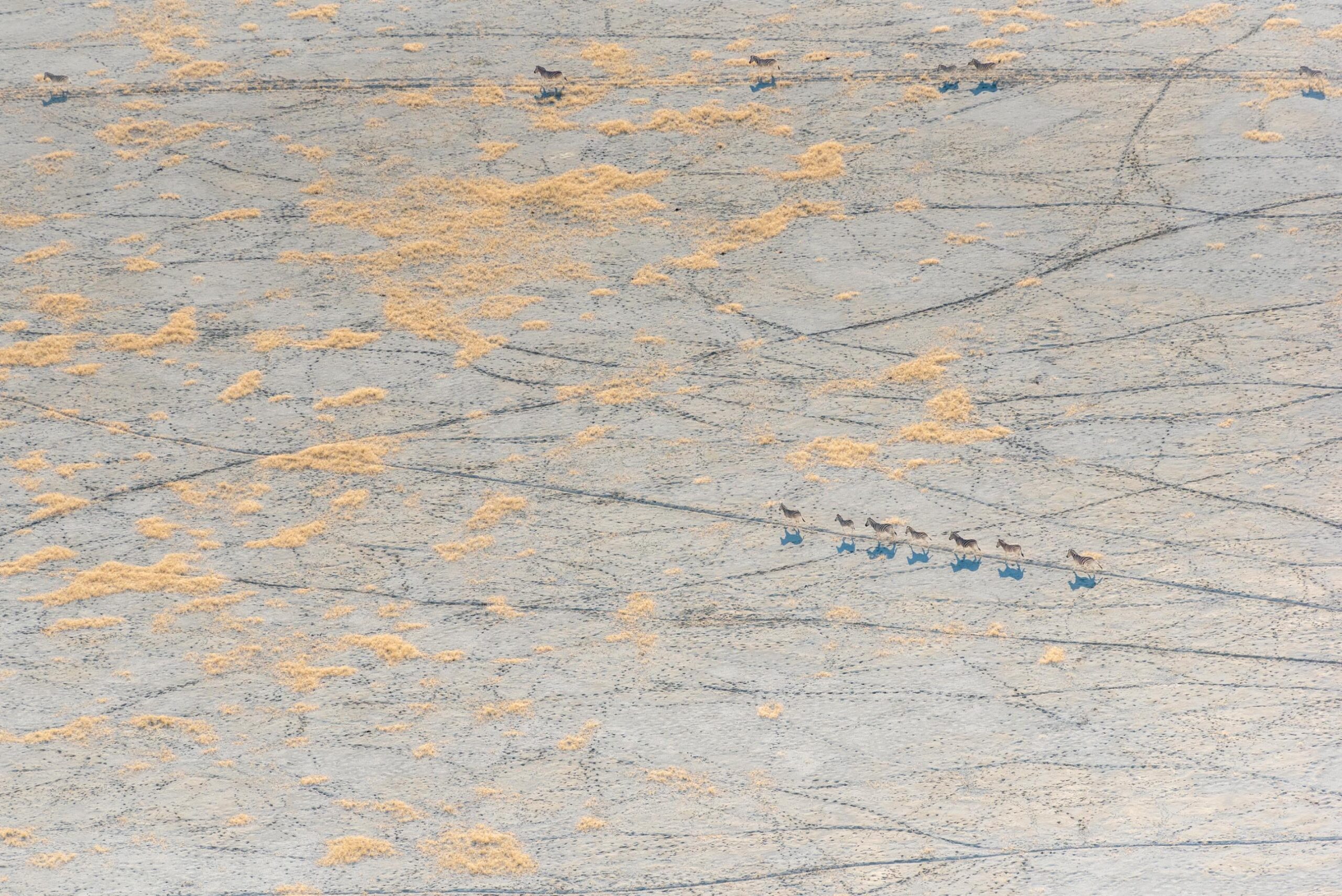

Most visitors and tourists to Namibia’s flagship park are greeted with stunning sights of the vast, shimmering expanse of the pan as they navigate their way along scenic routes. Every now and again, specks of wildlife can be seen in the distance, traversing parts of the pan, leaving one pondering the fact as to what could possibly draw them to such a seemingly barren, desolate wasteland.

Don’t be fooled. This perception could not be further from the truth when your perspective changes completely—not from ground level in your safari vehicle, but from lofty heights as you soar above the pan in a two-seater aeroplane with open windows, juggling three camera bodies in a tight space, holding on with a death grip to prevent them from tumbling down from a height of 500m!

A whole new world unfolded before my wondrous eyes, stunning all senses!

I had the immense privilege of photographing the Etosha Pan for five glorious days, flying in the best light for three hours at dawn and again late afternoon to just before sunset.

The experience was breathtaking, and surreal, and the landscape equally so. Sometimes, during seasons of exceptional rainfall, locally known as efundja, the pan floods through the Ekuma River from the Omadhiya lakes, a series of extensive, shallow grassy pans that merge into large bodies of water during periods of flooding. The pan also receives occasional inflow from the Omuramba Owambo, which drains into Fischer’s Pan at Namutoni. When flooded, Etosha Pan is transformed into a shallow wetland paradise, where huge flocks of lesser and greater flamingos, pelicans and other waterbirds arrive to feed and breed.

The sight of thousands of flamingos flying in various formations over the partly water- filled pan is simply breathtaking and one of nature’s great spectacles. On 19 June 1995, the Etosha Pan became a Ramsar site and a wetland of international importance.

The water that reaches the Omadhiya lakes and the pan eventually evaporates, leaving salt deposits that were carried downstream behind. Due to evaporation over long periods, various soils are extremely salty and compacted into complex, crusty layers. Salt-loving grasses and halophytic plants manage to grow in less saline soils, and bizarre landscapes of all shapes, patterns and colours are created. The main pan and smaller pans are scoured by relentless winds, thus shaped by wind deflation. Thick layers of salt deposits often fringe the pans and watercourses in various forms, resembling thick layers of white icing, blown into thin whisps in places. Vibrant hues of various colour variations are a spectacle to behold in narrow watercourses and seepages along the pan’s edges, as well as the Ekuma and Oshigambo rivers. These are created by the different salt crystals, bacteria and phytoplankton reflected in the water at different angles and times of day.

Thousands of tracks left by wild and birdlife are visible on parts of the pan’s surface, testament to the fact that there is life on the pan. Small islands and tracts of grasslands, especially in the region of the Ekuma River, sustain life and are frequented by wildlife in search of water, sweet grasses, and mineral deposits. Ostriches, for instance, often prefer to breed a few kilometres into the pan, seeking safety from predators.

I was able to document a pride of six lions for three days, first seeing them reclining in a lush, green, dense bed of reeds near the pan’s edge and then dramatically a day later when they were feasting on a meal of zebra on the white expanse of the pan. A final sight of them early the next morning, reclining satedly next to the Springbokfontein waterhole in an alien, lunar landscape from a bird’s-eye perspective, left me in awe.

Many waterholes like Sueda, Salvadora and Charitsaub offer a completely different perspective when viewed from above, offering a glimpse at what lies further away to the pan side. Many seepages occur at intervals at the edge of the pan, the water often reflected in brilliant hues of green, purple, orange and yellow. They, too, sustain life and attract a great number of wildlife.

One afternoon, the most bizarre sighting was that of a spring erupting on the pan, seemingly from nowhere. It was reminiscent of the shape of a painter’s palette and sported a myriad of different colours.

The pan revealed itself to me as a fairytale wonderland, a place of stark contrasts and extreme, abstract, artistic beauty. It was a life changing experience, one that left an indelible impression on my very soul… TN

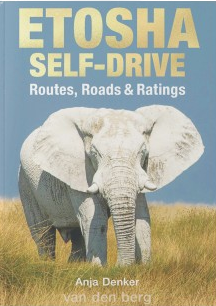

Editor’s note:

Few people have the immense privilege of experiencing Etosha from this special vantage point. Anja’s incredible photographic library and vast knowledge and experiences of Etosha National Park can be enjoyed in her new guidebook – Etosha Self-Drive: Routes, Roads & Ratings – available at local bookstores, Amazon, HPH Publishers or email anja@pumpsol.com.na.

More to explore

WILDERNESS NAMIBIA BRINGS RELIEF AMID WORST DROUGHT IN DECADES