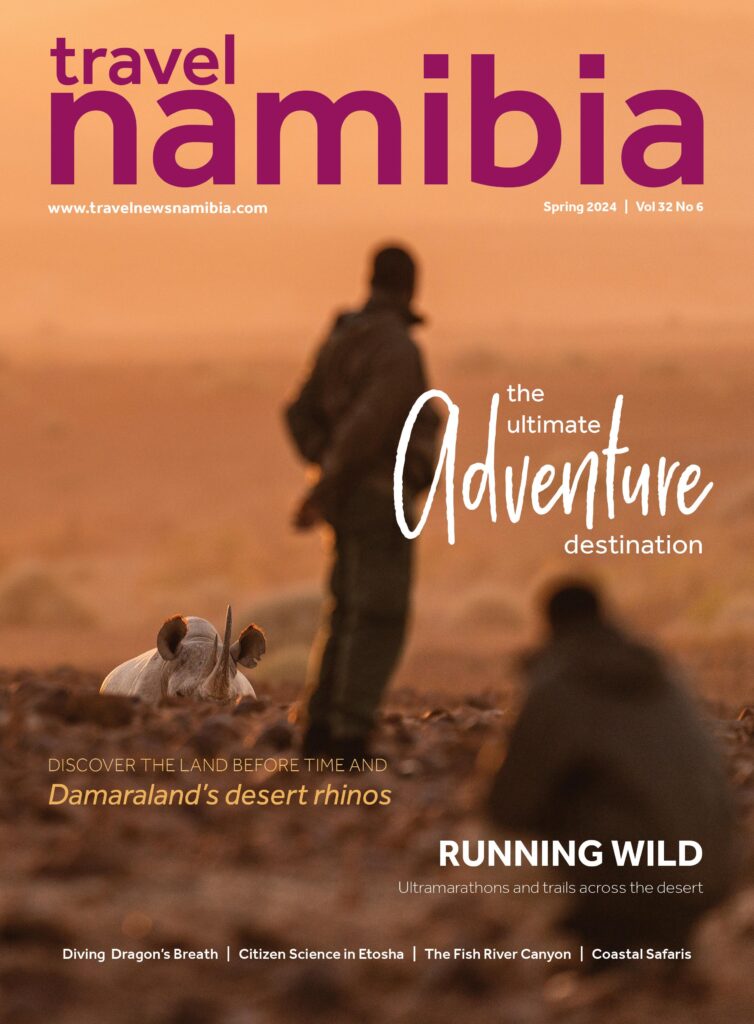

The land before time

Desert Rhino Camp

Text Christine Hugo | Photographs Wilderness

From the Spring 2024 issue

A honeybee sits on the windscreen of the aeroplane. The pilot hesitates. It is time to depart, but she does not want to harm the bee. She waits another minute and starts the engine. The propeller spins, and we begin to move forward. The bee ups and goes…

Far below, the landscape moves like a silent movie, backwards through millennia.

The colour fades to sepia. Stubble becomes stretch marks.

Then: barren, dry plains, flat-topped mountains and sandstone cliffs. Petrified energy of spent volcanoes.

Harsh, brutal and breathtakingly beautiful.

We land on a strip of gravel and disembark. In utter disbelief and wonder, my three co-passengers from Mexico observe the strange, new, old world.

How is it possible to be here at the end of the world?

For this is quite literally where we are, having just flown over a tiny dot on the map called Wêreldsend – which means world’s end.

The natural history museum of time, the ancient, unapologetic earth that is Damaraland, the desert that is the last and only one where wild black rhino have adapted to. This is their home. Heaven knows how.

From the airstrip, the specialised Land Cruiser rolls over gravel and rock. I grew up travelling through different terrains in various vehicles, the first of which was an old white Land Rover with very uncomfortable 90-degree seats and a lot of charm.

Since then I’ve experienced every possible mode of transport over rocks and dunes, seas of sand and roaring rivers.

This game viewer is unlike anything I have seen before. Everything has been thought through meticulously – ergonomics, comfort, convenience, excellence – from the individual little fridges between solid, comfortable bucket seats – stocked with cold water, beer and cooldrinks – to the tiny binoculars and every possible hook, nook and cranny you might need for holding, hanging, or storing.

“How is it possible?” my new friend from Mexico asks. “How do people build anything here? How do they live here? It is so far from anything.”

After rounding the last bend to the lodge, our driver, Bons, pulls over by a large bush with slender grey-green stems – Euphorbia damarana, poisonous to humans but not to rhinos or gemsbok.

Should humans even be here? I’m not sure that was the plan…

And yet, we arrive at Desert Rhino Camp to the welcome serenade of a jubilant and smiling choir. A wet cloth for dusty hands, welcome drinks and an invitation to enter while other necessary reminders of our previous worlds, like luggage, are swiftly and quietly taken care of.

I learn quickly that the carefully curated airport taxi was just an introduction to how everything is done at Desert Rhino Camp. Mindful. Attentive. Detailed.

The newly renovated Desert Rhino Camp’s interior design is understated elegance. It is a haven of organic shapes, textures, and natural hues that feed off the landscape.

Fire circles, cosy corners, and the curvy, elongated lounge and dining space serve as an auditorium from where to gaze at the landscape before you. For all the luxurious aesthetic of the lodge, the landscape demands centre stage, always luring your eyes up and away. As long as you are here, you will remain captive.

You will serve its magnitude and remain under its spell. So you might as well surrender.

It would have been enough, just this.

But then Bons takes us on a sunset excursion.

The gentle rocking of the game viewer. Wind in my hair.

Bons tells us the stories of this 130-million-year-old landscape. He speaks of basalt and oxidation, air pockets and veins that produced cobalt and crystal formations, of how this phantasmagorical place came to be.

I am spellbound. This man knows. He knows the land, the rocks, the history. He knows so much about every bird, antelope and ant. He points out shepherd trees and deciphers faintly visible spoor. But there is a special reverence in his voice when he speaks about them.

“This is it,” he says. “The last desert-adapted black rhinoceros in the world…”

We nod.

Bons is not convinced that we grasp the enormity of this phenomenon: “They receive no help, no water pumped to waterholes, no food supplementation or interference whatsoever to make their lives easier. If you were to bring black rhino from elsewhere to live here, they would suffer. These rhinos are the only ones of their kind.”

We are converted. We sense the presence of the prehistoric beasts, although Bons says that the area is so big that it is like finding a needle in a haystack. The only reason there is any chance of encountering them is because of the relentless and diligent work of Save the Rhino Trust, who employ people from local communities and train them to track and guard these prime specimens from poachers.

The love story between Desert Rhino Camp and Save the Rhino Trust is a beautiful one. Desert Rhino Camp originated as a field station for rhino protection work and proceeded to join forces with the formidable NGO that is Save the Rhino Trust and engaged with three local communities to join the cause.

Incorporating the local residents as partners in both the hospitality industry and the conservation operation completely changed the narrative and prospects of their communities. For the first time ever, the people here had opportunities to find employment, receive training and develop their potential. People who knew this land better than anyone in the world, who previously had to kill off predators to protect the desperate attempts at keeping livestock and were easy targets for cunning poachers with deep pockets who needed a hand on the ground, now had agency to protect the golden geese that brought them employment, economy and so much pride. And nobody was more equipped to do so than the inhabitants of this land.

My new foreign friends’ excitement at the sight of a couple of giraffes humbles me to the privilege of living in a country where wild, exotic animals are almost taken for granted. I look with new eyes and see, once again, the magnificence.

“A herd of giraffes is actually called a tower of giraffes,” Bons says.

No, we didn’t know that.

Bons whips out a classy sunset cocktail bar in the middle of nowhere. The sun drops like the curtain after a spectacular stage production. We toast to new friends and the wonder of the wilderness around us.

A chilly winter ride back to camp sends us to our rooms for hot showers and proper padding before dinner.

In the luxurious canvas-and-stone tented rooms, everything is, yet again, just so. Lush bedding, colours and textures, light fixtures and power sockets are all exactly where you need them to be, as effortlessly elegant as nature itself.

We meet up for dinner, warm water bottles for our laps. Our waiter, Water, is attentive and intuitive to our every move. My companions and I are at a loss for words yet again. How can a kitchen and a cook produce such exquisite, wonderfully prepared, beautifully presented dishes so far from civilisation? Ingrid Noeh Tewes had brought her two young adult daughters to Africa in celebration of her sixtieth birthday. “We knew it would be wonderful, but we didn’t expect this. We could never have imagined this…”

To see the beautiful and worldly youngsters equally moved by what they have seen and experienced makes me wonder what exactly it is about this place that transcends age, nationality, culture and experience.

Perhaps this particular corner of the earth is one of the last outposts of pure existence. It resonates with the soul and affects you on a cellular level, an existential, carnal recognition. It is not for everyone. It is not a zoo. Or a game park for instant gratification.

You work hard to see one of the last remaining desert- adapted black rhinos. A whole day’s excursion with an expert guide and the devoted Save the Rhino Trust trackers might secure you a single, or if all the stars align, two or three sightings. It requires having lunch in a dry riverbed (tables, tablecloths, cold wine, gourmet picnic – not an inconvenience by any measure), driving for hours and hours over rough terrain, looking, waiting. It demands tremendous respect and obedience, once located, following the tracker in a single file, only as far as they know you can safely go without disturbing or provoking the rhinoceros.

Exhausted and euphoric, the visitors attempt to relay their impressions of the day back at camp. Sophia has taken thousands of photographs, but not enough. “I don’t want to leave,” she tells her mother.

Me neither.

Around the fire, where the chef is busy with another five-star barbeque on the grid, Bons tells us stories of growing up in Damaraland. How, as young boys, they would taunt the rhinos, the bravest earning himself the lion’s share of the other boys’ dinners.

Now, when he speaks about these last remaining free-roaming animals with a price on their heads and the very real and continuous threat of their disappearance, it is with reverence and passion. It is evident that he loves his job and he really, really loves his rhinos. “You do not know the difference that you make by being here, investing in our communities, how our lives have changed…”

After a lifetime of living here, he still cannot stop photographing animals, sunsets and trees. He shows us reels and reels on his phone with unwearied enthusiasm. He has seen it all and he keeps on seeing.

Ingrid gives up trying to hold back the tears as the staff sing to us, here under the stars, moving, clicking their special vernacular sounds, humming and dancing. Angelica with the angelic voice. Water with the ready smile and shining eyes, excited that he is learning to drive with the prospect of following in his uncle Bons’ footsteps to become a guide. The spell of Damaraland and Desert Rhino Camp stayed with me for days after I returned. It changes me every time. Yet I think it changes you back to your selfest self.

Perhaps when the world was created, the dust that I will return to be was already there, waiting for me. Maybe we are all ancient. And I am Damaraland. TN

More to explore

Discover Airlines launches a new direct flight between Windhoek and Munich